1879 was a crucial year for the National League. After enduring yet another multiple franchise loss (Indianapolis and Milwaukee), Hulbert acted decisively to stabilize the league and destabilize its chief rival (not in the sense of a competing major league, but rather a different way to organize professional clubs), the International Association, by expanding to eight teams. The biggest coup was pilfering the IA of its top two teams in 1878, Buffalo and Syracuse. Also added were Troy, the strognest club in the New York State Association, and Cleveland, a respectable independent club (32-20 in 1878) that had the added bonus of represented a sizeable city. With three of the additions being in the east, the NL re-established itself as a national circuit rather than a predominately midwestern one (although it remained on the outside looking in of major eastern cities like New York and Philadelphia).

With the larger configuration, the schedule was expanded from 60 games to 84, which also allowed NL clubs to be less reliant on exhibitions with non-league teams for revenue. David Nemec cites this season as the one in which playing in the National League gained a special status, a “major league” feel, due largely to these changes.

The playing rules got their customary annual tweak. The Spalding ball, manufactured of course by Al Spalding, became the official league ball. Fouls had to be caught on the fly, rather than on the first bound, and pitchers could now be fined for intentionally hitting batters (although the batter did not yet earn first base for his trouble). The width of the pitcher’s box was reduced from six feet to four, pitchers could not turn their back completely during a delivery, and every bad pitch was called a ball, rather than every third. Since the number of balls needed for a walk went to nine rather than three, this rule did not affect the game, but it brought practice closer to modern standards. The first batter in the next inning was now the next batter in the order who had not completed a plate appearance, rather than the one that followed the last man retired. Finally, batters were now automatically out if the catcher made a clean catch on strike three. This encouraged catchers to play closer to the plate.

The disappointing Chicago White Stockings looked as if they would get redemption; they got off to a 6-0 start and led the race into August. At that point, though, their new manager and star Cap Anson was sidelined by a liver illness, and Chicago fell out of the race, leaving it to natural rivals Boston and Providence. Providence was now skippered by George Wright, who was not on the same outfit with brother Harry for the first time in at least a decade.

The schedule set up perfectly, as the two teams were set to play the final six games of the season head-to-head starting on September 23. The Grays entered the series with a three game lead over the Red Caps, so Boston would need to take five to capture their third straight pennant. They got the first game 7-3, but game two on the 25th and game three the next day went to the Grays, 15-4 and 7-6. Providence would win two of the remaining three games for a victorious margin of five.

Only Syracuse left the league at the end of the season, making for the most stable off-season in terms of franchise intrigue yet.

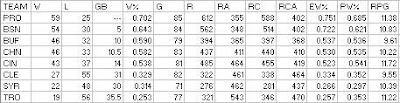

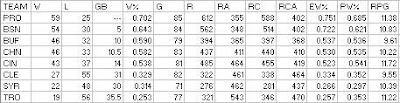

STANDINGS

Providence led the league in both EW% and PW%. Chicago declined in terms of those two gauges, but this time they managed to outplay them under new skipper Cap Anson. All of the returning teams, plus Buffalo, managed to finish above .500 and were separated top to bottom by fourteen games, while the new entries from Cleveland, Syracuse, and Troy were seventeen games behind the bottom team in that pack, Cincinnati.

In 1879, the league hit .255/.271/.329 for a .094 SEC, with 5.31 runs and 24.60 outs per game.

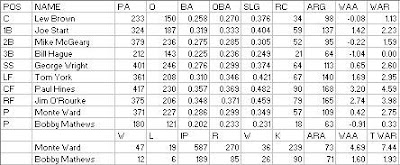

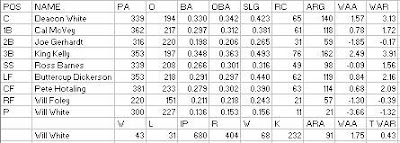

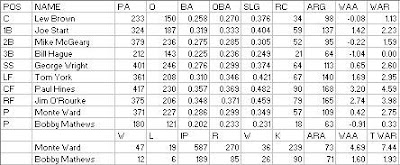

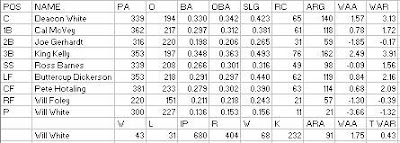

PROVIDENCE

George Wright won the pennant in his first (and only) season as a big league manager. The Grays were helped when he brought Jim O’Rourke with him from Beantown; they also added Chicago’s Joe Start, and brought Mike McGeary and Bobby Mathews back into the league after they were absent in 1878. They were the only team in the league to have two good pitchers--Boston had one great pitcher and one solid but below-average pitcher; Buffalo had two average pitchers. The Grays’ #2 pitcher, Bobby Mathews, actually had a slightly better ARA than Monte Ward, a luxury no one else had in 1879.

Despite the pennant, attendance in Providence was poor, averaging around 1,000 per game. The big draws were games with Boston, the natural geographic rivals in addition to being their chief pennant challenger.

This was Wright’s only season because as a manager because he would retire at the end of the season to tend to his sporting goods business. While he would pull a Michael Jordan, he was never again the same player

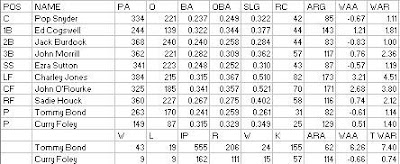

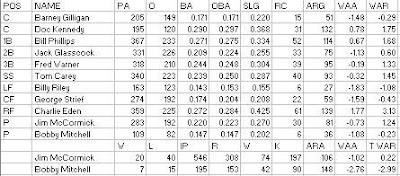

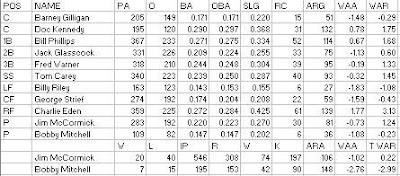

BOSTON

The Red Caps were hurt by the defections of George Wright and Jim O’Rourke to Providence. Bringing Charley Jones in from Cincinnati helped to offset his loss, and Ed Cogswell, Curry Foley, Sadie Houck, and especially Jim’s brother John O’Rourke were productive rookie finds. John was actually a year older than Jim, but was making his NL debut at age thirty. The WAR battle in the family went to Jim, but only +4.0 to +3.8.

Once again, Harry Wright was forced to play musical chairs with his infield; this time, Morrill and Sutton moved back to their 1877 positions, with rookie Cogswell manning first base.

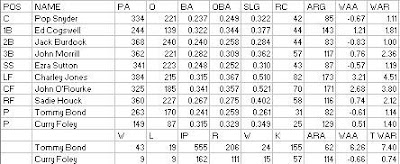

BUFFALO

The Bisons had a very solid debut season, illustrating historians’ claims that the earliest NL teams were not significantly stronger than the top independent and IA clubs. It is not surprising when considering the fact that the 1878 Bisons beat every team in the National League in exhibition play, with an overall record of 10-7 (Joe Overfield, SABR’s Road Trips). For the second year in a row, John Clapp was the manager for a first year team (he led the Indianapolis Blues in 1878). His team was composed of NL rookies except for himself, Chick Fulmer and Bill Crowley (each former Louisville Grays), Dave Eggler (last with the White Stockings in 1877), and Davy Force, who last played with St. Louis in 1877.

Captain Force opposed the Bisons’ move to the NL, and even wrote a letter to team management espousing his position; his main objection was the financial turmoil often present in the NL. One wonders if there was not a tiny bit of self-preservation involved; after all, his offensive production was pretty putrid.

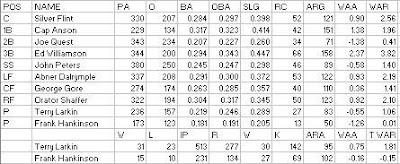

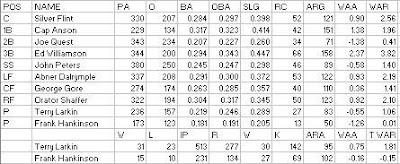

CHICAGO

While the promising season was derailed by Anson’s illness, he earned the respect of the brass including Al Spalding in a way that his predecessor Bob Ferguson could not. According to Bill James in the 1990 Baseball Book, Anson was involved in an argument with an umpire one day when Spalding decided to come onto the field to put his two cents in. Anson shifted his focus and went off on Spalding. When Spalding refused to leave the field, Cap “reminded” the ump that he could forfeit the game. At that point, Spalding left.

His club was bolstered by a wholesale raid of defunct Indianapolis that netted Silver Flint, Joe Quest, Ed Williamson, and Orator Shaffer (combined 8.9 WAR). Two players plucked from Milwaukee (ex-White Stocking John Peters and Abner Dalrymple) added another 3.6 wins, and rookie George Gore took over capably in center field.

Unfortunately, top starter Terry Larkin was hit by a line drive and was never the same, only appearing in five games with Providence in 1880. His personal life did not have a happy ending, either; some sources cite the line drive as a contributor to his future madness (he shot his wife in 1883 and later tried to duel with a saloon owner), but I find that a little hard to swallow.

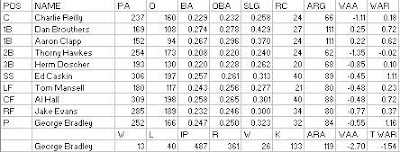

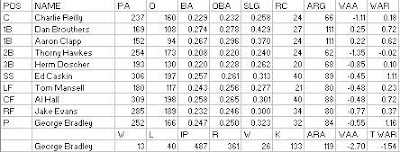

CINCINNATI

The Reds installed Deacon White as manager, replacing Cal McVey. White signed Ross Barnes, out of the NL in 1878, to play shortstop; Will Foley was brought back after one year in Milwaukee to replace the big loss of Charley Jones. White’s tenure was short and rocky; first, he infuriated powerful local sportswriter O.P. Caylor by hiring his own brother-in-law as scorer instead of Caylor. Caylor ripped him for moves like releasing pitcher Bobby Mitchell, leaving brother Will as the team’s only starter (he wound up tossing 680 of the team’s 726 innings and pitching 75 complete games out of the 81 they played).

White was removed after sixteen games while the team was on its first east coast trip, and McVey was put back in charge. That did not stop the soap opera, though, as rookie shortstop Mike Burke (who had lost his job to Barnes) fought with McVey in public view on the field after his release. The Reds’ salary structure (McVey, Deacon White, and Barnes all made $2,000 while the other players made $800) was blamed for the dissension by some observers. Joe Gerhardt, one of the better second baseman in the league in 1878, saw his production plummet (+2.1 to -.2 WAR). At the end of the campaign, all players were released and the franchise withdrew from the NL, only to be quickly replaced by another Cincinnati club.

Also gone from the scene was Cal McVey, who was done in the NL at age 30 despite a solid +1.7 WAR season. McVey moved to California and there are sketchy details of him playing for various western teams in the 1880s. He had played for a number of significant teams--the original Red Stockings of 1869, the 1872, 74, and 75 pennant winning Red Caps, and the 1876 White Stockings that won the NL’s first pennant.

CLEVELAND

Ohio and New York became the first states ever to have multiple National League teams (New York with three) with the addition of Buffalo, Cleveland, Syracuse, and Troy. The Blues fielded a team comprised largely of NL rookies. Only McCormick and Warner (Indianapolis), Carey (Providence), and Mitchell (Cincinnati) had played in the NL in 1878. Charlie Eden had been a reserve for the White Stockings in 1877.

According to David Nemec, July 19’s game between Cleveland and Boston, matching Bobby Mathews against Curry Foley, was the first NL game in which each team had a southpaw starting pitcher.

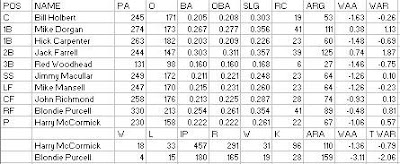

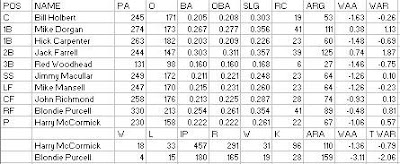

SYRACUSE

The Stars had a higher W% in the 1878 IA than the Bisons, but Buffalo won the pennant as the rules called for the team with the most wins to be the champion. Their bad fortune continued when their former league-mates emerged as a quality club while the Stars stumbled their way to a 22-48 record. The makeup of the team was apparently mostly the same as the 1878 IA entry; only Bill Holbert (Milwaukee) had played in the NL in 1878, and manager Mike Dorgan’s 1877 stint in St. Louis was the only other league experience among regulars.

A couple of interesting anecdotes on this team come from Lloyd Johnson and Brenda Ward in the Bill James Encyclopedia program. One is that “Blondie” Purcell was so called because he used peroxide on his hair. The RF/P would wind up in Cincinnati by the end of the year. The other is that Dorgan was a key part of the Star teams of 1876 and 1878, but “his marriage in 1879 broke up the jolly team of bachelors and was the social event of the year in Syracuse”. Perhaps that is the cause of Syracuse’s flop in the NL.

Regardless of what it was, Syracuse had trouble supporting a team from the start. Management attempted to get an exemption from the mandatory fifty-cent admission charge, but was unsuccessful. On September 11, the team disbanded, having played only 71 games of the 84 game schedule.

TROY

The Trojans brought in Bob Ferguson, the White Stockings’ failed skipper of 1878, to manage a team made up largely of players culled from IA teams. Ferguson only gave himself 127 PA, although his 99 ARG and +.6 WAR was much better than what regular third baseman Herm Doscher produced. The only regular besides Ferguson with NL experience was pitcher George Bradley, last seen with Chicago in 1877.

That the team survived is a bit surprising; the other small city NL club, Syracuse, did not survive, and Troy averaged only around 400 patrons. They were hurt by the loss of their traditional rivalry with Albany, a club which had also applied for NL membership but was rejected.

Interesting to note here is the performance of the two first baseman: 23 year old Aaron Clapp and 21 year old Dan Brouthers, each rookies. Brouthers got 169 PA and Clapp got 152; Brouthers hit for a slightly better average (seven points) and a lot more power (.155 ISO to .103), but Clapp drew more walks and their overall offensive production were essentially the same (111 ARG). Brouthers comes out a bit better in value metrics due to his extra PA. After 1879, their career paths would diverge greatly. Clapp would never again play in the major leagues, and Brouthers…well, we’ll see his exploits in later installments.

Leaders and trailers:

BATTING AVERAGE

1. Paul Hines, PRO (.357)

2. Jim O’Rourke, PRO (.348)

3. King Kelly, CIN (.348)

Trailer: Will White, CIN (.136)

Trailing non-pitcher: Barney Gilligan, CLE (.171)

ON BASE AVERAGE

1. Jim O’Rourke, PRO (.371)

2. Paul Hines, PRO (.369)

3. Charley Jones, BSN (.367)

Trailer: Will White, CIN (.153)

Trailing non-pitcher: Barney Gilligan, CLE (.171)

SLUGGING AVERAGE

1. John O’Rourke, BSN (.521)

2. Charley Jones, BSN (.510)

3. King Kelly, CIN (.493)

Trailer: Will White, CIN (.156)

Trailing non-pitcher: Bill Holbert, SYR (.201)

SECONDARY AVERAGE

1. Charley Jones, BSN (.276)

2. Ed Williamson, CHN (.228)

3. John O’Rourke, BOS (.205)

Trailer: Bill Holbert, SYR (.004)

Holbert’s secondary contributions amounted to just one solitary walk in 245 PA. I believe that this is the lowest Secondary Average of all-time.

RUNS CREATED

1. Paul Hines, PRO (90)

2. Charley Jones, BSN (82)

3. Jim O’Rourke, PRO (79)

4. King Kelly, CIN (76)

5. John O’Rourke, BSN (70)

ARG

1. Charley Jones, BSN (173)

2. John O’Rourke, BSN (171)

3. Paul Hines, PRO (168)

4. Jim O’Rourke, PRO (165)

5. King Kelly, CIN (162)

Trailer: Will White, CIN (21)

Trailing non-pitcher: Barney Gilligan, CLE (51)

WAA

1. Charley Jones, BSN (+3.2)

2. Paul Hines, PRO (+3.2)

3. Jim O’Rourke, PRO (+2.7)

4. John O’Rourke, BSN (+2.7)

5. King Kelly, CIN (+2.5)

Trailer: Will White, CIN (-3.7)

Trailing non-pitcher player: Joe Gerhardt, CIN (-1.8)

WAR

1. Paul Hines, PRO (+4.6)

2. Charley Jones, BSN (+4.5)

3. Jim O’Rourke, PRO (+4.0)

4. King Kelly, CIN (+3.9)

5. Ed Williamson, CHN (+3.8)

Trailer: Will White, CIN (-1.3)

Trailing non-pitcher: Hick Carpenter, SYR (-.7)

I have included pitchers in the trailer lists because, unlike today where you have a five man rotation and pitchers generally only get two or three PAs a game, at this time you had one pitcher, pitching a majority of your games and completing most of those. Pitchers got enough PA to qualify (I have been using 200 as a the minimum), so why not include them? White’s hitting was horrid, and that cost the Reds real games (White had a 21 ARG; the next lowest pitcher was his ex-teammate, Bobby Mitchell of Cleveland, who put up a 36, and did it in 145 less outs.)

ARA

1. Tommy Bond, BSN (62)

2. Monte Ward, PRO (73)

3. Will White, CIN (91)

Trailer: Blondie Purcell, SYR (159)

WAA

1. Tommy Bond, BSN (+6.3)

2. Monte Ward, PRO (+4.7)

3. Will White, CIN (+1.7)

Trailer: Blondie Purcell, SYR (-3.1)

T WAR

1. Monte Ward, PRO (+7.4)

2. Tommy Bond, BOS (+7.4)

3. Pud Galvin, BUF (+2.4)

Trailer: Bobby Mitchell, CLE (-3.0)

My all-star team:

C: Deacon White, CIN

1B: Joe Start, PRO

2B: Chick Fulmer, BUF

3B: King Kelly, CIN/Ed Williamson, CHN

SS: George Wright, PRO

LF: Charley Jones, BSN

CF: Paul Hines, PRO

RF: Jim O’Rourke, PRO

P: Tommy Bond, BSN/Monte Ward, PRO

MVP: CF Paul Hines, PRO/LF Charley Jones, BSN

Rookie Hitter: CF John O’Rourke, BSN

Rookie Pitcher: Pud Galvin, BUF

At second base, Chick Fulmer and Jack Farrell each had 1.9 WAR. Palmer’s FR had Farrell at -14 and Fulmer at +18, making this an easy choice. At third, Kelly was +3.9 WAR and Williamson +3.8; in FR, they were +10 and +18, respectively. If you take the FR as equally reliable to the batting figures, that would make Williamson more valuable; I don’t, but it’s more than enough to make it a tie in my book.

The choice at pitcher between Bond and Ward comes down to the choice between superior pitching and superior hitting. Bond beat Ward in pitching WAA 6.3 to 4.7, but Ward’s hitting would have provided value at any position (57 RC, 109 ARG). In the end, they are close--if you want to view this as a pitching-only honor, than Bond is your man. In terms of overall value, I see it as too close to call.

I also split the baby on the MVP question. Hines’ 4.6 WAR was slightly better than Jones’ 4.5, but remember that all outfielders have been lumped together, with no recognition that Hines played center and Jones played a corner. In Palmer’s FR, Jones was +13 and Hines was +5; but again, Hines’ status as a center fielder can’t be ignored. When dealing with things so far in the past with limited information, I think it’s best to err on the side of caution, and I have done that with these choices.