Offensive performance by position (and the closely related topic of positional adjustments) has always interested me, and so each year I like to examine the most recent season's totals. I believe that offensive positional averages can be an important tool for approximating the defensive value of each position, but they certainly are not a magic bullet and need to include more than one year of data if they are to be utilized in that capacity.

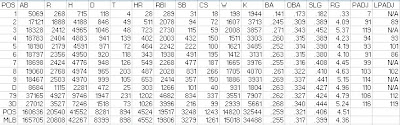

The first obvious thing to look at is the positional totals for 2011, with the data coming from Baseball-Reference.com. "MLB” is the overall total for MLB, which is not the same as the sum of all the positions here, as pinch-hitters and runners are not included in those. “POS” is the MLB totals minus the pitcher totals, yielding the composite performance by non-pitchers. “PADJ” is the position adjustment, which is the position RG divided by the position (non-pitcher) average. “LPADJ” is the long-term positional adjustment that I use, based on 1992-2001 data. The rows “79” and “3D” are the combined corner outfield and 1B/DH totals, respectively:

The 2011 results were most notable for the poor performance by third basemen and the pathetic effort by left fielders, who were slightly less productive than the average non-pitcher. After a down 2010, DHs rebounded to a respectable 110. The other positions were fairly close to their historical norms, and pitchers avoided setting a new all-time low, although the difference between 7 and 5 is negligible.

Speaking of pitchers, here are the aggregate park-adjusted totals for NL pitching teams. This analysis is based on simple ERP, and thus ignores sacrifices and the other situational goodness that makes pitcher hitting such an exciting and integral part of our national pastime:

Milwaukee ranked second and Arizona first last year, but on the other hand the Mets were third in 2010 and dead last in 2011. AL pitchers don’t get enough opportunities to bother with a chart, but for trivia’s sake, Baltimore’s pitchers raked .405/.405/.630, while Kansas City’s failed to reach base in eighteen plate appearances.

Moving on to positions that are actually expected to hit, I figured park-adjusted RAA for each position. The baseline for average is the overall 2011 MLB average RG for each position, with left and right field pooled. The leading team at each position was as follows (these are generally unsurprising so I’ll spare you a big chart):

C--DET, 1B--DET, 2B--BOS, 3B--CHN, SS--NYN, LF--MIL, CF--LA, RF--TOR, DH--BOS

The only one of these that was a bit surprising to me even after looking at the final stats for individuals was the Cubs’ third basemen (led of course by Aramis Ramirez). But a lot of the usual suspects at third base had injuries and other issues this year (Longoria, Zimmerman, Wright, Youkilis).

Now the worst performance at each position, along with a column displaying the team leader in games played at that spot:

It’s mostly a coincidence that all of the worst-hitting positions were from AL teams, although they do generally get more PA in which to drive down their RAA. I wrote about the Twins and Angels catchers a little in the previous post, but note here that Houston’s catchers were second last with -31 RAA and the Angels managed -29. The continuing inability of Seattle to generate offense is a marvel, and Juan Pierre is an appropriate banner carrier for 2011’s crop of poor hitting left fielders.

The following charts give the RAA at each position for each team, split up by division. The charts are sorted by the sum of RAA for the listed positions. As mentioned earlier, the league totals will not sum to zero since the overall ML average is being used and not the specific league average. Positions with negative RAA are in red; positions with +/- 20 RAA are bolded:

Third base and shortstop led the Mets to the highest infield RAA in the NL. Atlanta tied for the lowest outfield RAA in the NL. There must be something wrong with my spreadsheet as surely the Phillies first basemen combined for more than 8 RAA, led by their perennial MVP candidate.

St. Louis was the only team in the game to be above average at every position, and really stood at out at the three biggest offensive positions. Their outfield combined to lead MLB in RAA. Milwaukee’s offense was structured similarly, although right field did not stand out and they gave a lot of it back with a black hole at third base. The Cubs’ outfield production was evenly distributed and combined to tie Atlanta for the lowest mark in the NL. Pittsburgh’s infield tied for the NL’s trailer spot. Houston got decent production in the outfield but nowhere else.

The fact that the Los Angeles infield tied for the fewest RAA in the NL and yet the offense combined to lead the division should give you a quick idea on the offensive character of the NL West. While the World Series title makes it easy for some to overlook, San Francisco’s offensive struggles are persistent and pitching can only take you so far.

Boston’s offense was terrific despite right field, leading the majors in infield RAA. Toronto pulled a neat trick by combining for -17 RAA from the outfield despite having Jose Bautista.

Kansas City led the AL in outfield RAA, which not many would have predicted from Alex Gordon, Melky Cabrera, and Jeff Francoeur. Cleveland’s outfield was second-worst in the majors, and under normal circumstances -62 from the outfield would stick out more. The best thing that can be said about Chicago’s -98 RAA is that it was balanced -49/-49 between infield and outfield, with catcher and DH nearly average (+2/-2).

Texas kept the AL West from looking like it’s NL counterparts. Chris Iannetta and some guy whose name I can’t remember should do wonders for LAA. Oakland’s -50 runs from the infield was the worst in the majors, almost all driven by dreadful production at first base. And then there’s Seattle. What can one say about Seattle? Every outfield position was at least -20 (only five other outfield spots across the other 29 teams were at -20). Catcher, third base, and DH also stood out for the hapless Mariners.

Earlier I displayed some long-term positional adjustments that I’ve used over the years. It dawned on me in September that those were based on the ten-year period from 1992-2001, and that at this point, none of the most recent ten years are included in the sample. So I figured it would be an opportune time to recalibrate my position adjustments, using the ten years from 2002-2011 as the basis.

I figured two sets of PADJs; one which compared each position to the overall league average (including pitchers), and one that compared it to the league average less pitchers. There is very little difference, of course--the ones compared to the average including pitchers tend to be one or two points higher. This table compares the 1992-2001 and the 2002-2011 adjustments:

The big movers relative to 1992-2001 were the middle infield positions, improving offensively as first base/DH declined a little. In the end, though, the defensive spectrum one would draw based on offense doesn’t change at all, except for third base switching places with center field (and the differences were miniscule in both decades) to match Bill James’ spectrum.

A longer digression about the application of position adjustments, and some reasons why one might want to consider using offensive adjustments, will have to wait for another time, but would be appropriate here.

This spreadsheet includes the 2011 data by position.

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Hitting by Position, 2011

Monday, December 19, 2011

Hitting by Lineup Slot, 2011

I devoted a whole post to leadoff hitters, whether justified or not, so it's only fair to have a post about hitting by batting order position in general. I certainly consider this piece to be more trivia than sabermetrics, since there’s no analytical content.

The data in this post was taken from Baseball-Reference. The figures for each team's runs are not park-adjusted--I intended to do so, but unfortunately I had already written the body of the post before I realized that they’d been omitted. The Padres having the worst 2, 3, and 4 production in the NL should have alerted me to this sooner. Then I had to go back and remove some comments that make no sense when ignoring park effects, so now the post is just a skeleton. Oh well. RC is ERP, including SB and CS, as used in my end of season stat posts. The weights used are constant across lineup positions; there was no attempt to apply specific weights to each position, although they are out there and would certainly make this a little bit more interesting.

This marks a third straight season that the most productive lineup slot in the majors was the NL’s #3 hitters…Pujols, Votto, Braun and company. Despite all of the seemingly silly things managers do with their batting orders, it is comforting to know that, from the cleanup spot down, each subsequent spot is less productive. Of course, that doesn’t excuse the feeble performance of NL #2 hitters, who just edged out the #8 hitters as the least productive NL spot filled by real hitters.

Next, here are the team leaders in RG at each lineup position. The player listed is the one who appeared in the most games in that spot (which can be misleading as the presence of Mitch Moreland demonstrates):

Houston actually had the NL’s most productive hitters at two spots; of course, they were two bottom of the batting order spots in which nobody contributes anyway. The least productive lineup spots:

As you can see, Minnesota had the worst production out of both the #8 and #9 spots. What makes this truly impressive, though, is that Drew Butera was the leader in games played in both spots. One thing I had meant to include in my meanderings post but forgot was a comparison of Mathis and Butera’s basic batting lines as I present them in my end of season stats. Neither had enough PA to qualify for those lists, but their seasons were too bad to just ignore:

![]()

Mathis was intentionally walked twice; both came in a June 17 game at the Mets. No word on whether or not Ron Washington temporarily replaced Terry Collins.

Note that Houston’s #9 hitters (the best in the NL at 2.3 RG) almost managed to outhit their #8 hitters (worst in the NL at 2.5 RG).

The next chart displays the top ten positions in terms of RAA, compared to their league’s average for each spot. A lot of the same suspects pop up, of course:

And the ten worst positions:

Finally, this table has each team’s RG rank among the lineup slots in their league. The top and bottom three in each league have been noted, which make Boston and Seattle stand out (for opposite reasons, of course).

Here is a link to a Google spreadsheet with the underlying data. The RG and RAA figures in this one are park-adjusted as should have been done throughout this post.

Thursday, December 08, 2011

2011 Leadoff Hitters

This post kicks off a series of posts that I write every year, and therefore struggle to infuse with any sort of new perspective. However, they're a tradition on this blog and hold some general interest, so away we go.

This post looks at the offensive performance of teams' leadoff batters. I will try to make this as clear as possible: the statistics are based on the players that hit in the #1 slot in the batting order, whether they were actually leading off an inning or not. It includes the performance of all players who batted in that spot, including substitutes like pinch-hitters.

Listed in parentheses after a team are all players that appeared in twenty or more games in the leadoff slot--while you may see a listing like "BOS (Ellsbury)” this does not mean that the statistic is only based solely on Ellsbury's performance; it is the total of all Boston batters in the #1 spot, of which Ellsbury was the only one to appear in that spot in twenty or more games. I will list the top and bottom three teams in each category (plus the top/bottom team from each league if they don't make the ML top/bottom three); complete data is available in a spreadsheet linked at the end of the article. There are also no park factors applied anywhere in this article.

That's as clear as I can make it, and I hope it will suffice. I always feel obligated to point out that as a sabermetrician, I think that the importance of the batting order is often overstated, and that the best leadoff hitters would generally be the best cleanup hitters, the best #9 hitters, etc. However, since the leadoff spot gets a lot of attention, and teams pay particular attention to the spot, it is instructive to look at how each team fared there.

The conventional wisdom is that the primary job of the leadoff hitter is to get on base, and most simply, score runs. So let's start by looking at runs scored per 25.5 outs (AB - H + CS):

1. TEX (Kinsler), 6.8

2. MIL (Weeks/Hart), 6.5

3. BOS (Ellsbury), 6.4

Leadoff average, 5.0

ML average, 4.3

28. LAA (Izturis/Aybar), 4.0

29. STL (Theriot/Furcal), 3.9

30. WAS (Bernadina/Desmond/Espinosa), 3.9

Obviously you all know the biases inherent in looking at actual runs scored. It is odd to see St. Louis near the bottom as they had a good offense overall. Usually the leadoff hitters will manage to score some runs when they have Pujols, Holliday and Berkman coming up behind them whether they get on base that much or not.

Speaking of getting on base, the other obvious measure to look at is On Base Average. The figures here exclude HB and SF to be directly comparable to earlier versions of this article, but those categories are available in the spreadsheet if you'd like to include them:

1. CHN (Castro/Fukudome), .364

2. NYN (Reyes/Pagan), .364

3. BOS (Ellsbury), .362

Leadoff average, .324

ML average, .317

28. BAL (Hardy/Roberts/Andino), .287

29. SF (Torres/Rowand), .282

30. WAS (Bernadina/Desmond/Espinosa), .277

I would not have correctly identified the Cubs as having the highest OBA out of the leadoff spot in my first fifteen guesses, I don’t think. The seven point difference between the overall major league OBA and the OBA of leadoff men is a little smaller than it usually is, but last year the gap was just two points.

The next statistic is what I call Runners On Base Average. The genesis of it is from the A factor of Base Runs. It measures the number of times a batter reaches base per PA--excluding homers, since a batter that hits a home run never actually runs the bases. It also subtracts caught stealing here because the BsR version I often use does as well, but BsR versions based on initial baserunners rather than final baserunners do not.

My 2009 leadoff post was linked to a Cardinals message board, and this metric was the cause of a lot of confusion (this was mostly because the poster in question was thick-headed as could be, but it's still worth addressing). ROBA, like several other methods that follow, is not really a quality metric, it is a descriptive metric. A high ROBA is a good thing, but it's not necessarily better than a slightly lower ROBA plus a higher home run rate (which would produce a higher OBA and more runs). Listing ROBA is not in any way, shape or form a statement that hitting home runs is bad for a leadoff hitter. It is simply a recognition of the fact that a batter that hits a home run is not a baserunner. Base Runs is an excellent model of offense and ROBA is one of its components, and thus it holds some interest in describing how a team scored its runs, rather than how many it scored:

1. CHN (Castro/Fukudome), .339

2. NYN (Reyes/Pagan), .336

3. PIT (Tabata/McCutchen/Presley), .315

Leadoff average, .291

ML average, .285

28. SF (Torres/Rowand), .253

29. BAL (Hardy/Roberts/Andino), .253

30. WAS (Bernadina/Desmond/Espinosa), .247

You are probably starting to notice a lot of repetition in the leaders and trailers. Obviously a lot of these metrics measure the same thing in slightly different ways or measure similar things, so it’s to be expected.

I will also include what I've called Literal OBA here--this is just ROBA with HR subtracted from the denominator so that a homer does not lower LOBA, it simply has no effect. You don't really need ROBA and LOBA (or either, for that matter), but this might save some poor message board out there twenty posts, so here goes. LOBA = (H + W - HR - CS)/(AB + W - HR):

1. CHN (Castro/Fukudome), .344

2. NYN (Reyes/Pagan), .341

3. PIT (Tabata/McCutchen/Presley), .321

Leadoff average, .297

ML average, .292

28. BAL (Hardy/Roberts/Andino), .261

29. SF (Torres/Rowand), .257

30. WAS (Bernadina/Desmond/Espinosa), .252

In this presentation, the rank difference between ROBA and LOBA is barely noticeable.

The next two categories are most definitely categories of shape, not value. The first is the ratio of runs scored to RBI. Leadoff hitters as a group score many more runs than they drive in, partly due to their skills and partly due to lineup dynamics. Those with low ratios don’t fit the traditional leadoff profile as closely as those with high ratios (at least in the way their seasons played out):

1. LA (Gordon/Gwynn/Carroll/Furcal), 2.5

2. HOU (Bourn/Bourgeois/Schafer), 2.1

3. DET (Jackson), 2.0

Leadoff average, 1.6

26. WAS (Bernadina/Desmond/Espinosa), 1.2

28. KC (Gordon/Getz), 1.2

29. BOS (Ellsbury), 1.2

30. BAL (Hardy/Roberts/Andino), 1.2

ML average, 1.1

The presence of the Red Sox in the bottom three on this list should drive home the point about this not being a quality metric. The leadoff hitters that rank the lowest in R/BI are those that drive in almost as many runs as they score. If you had a leadoff hitter that was driving in many more runs than he scored, that might be cause for some reconsideration of your batting order, but having some scored/batted in parity is not inherently a bad thing.

A similar gauge, but one that doesn't rely on the teammate-dependent R and RBI totals, is Bill James' Run Element Ratio. RER was described by James as the ratio between those things that were especially helpful at the beginning of an inning (walks and stolen bases) to those that were especially helpful at the end of an inning (extra bases). It is a ratio of "setup" events to "cleanup" events. Singles aren't included because they often function in both roles.

Of course, there are RBI walks and doubles are a great way to start an inning, but RER classifies events based on when they have the highest relative value, at least from a simple analysis:

1. CHA (Pierre), 2.4

2. MIN (Revere/Span), 1.9

3. LA (Gordon/Gwynn/Carroll/Furcal), 1.8

Leadoff average, 1.0

ML average, .8

28. BAL (Hardy/Roberts/Andino), .6

29. BOS (Ellsbury), .6

30. MIL (Weeks/Hart), .6

Last year, the White Sox led handily in RER, due in large part to Pierre’s steals. This year, Pierre didn’t steal as many bases but still managed to slap his team to the top.

Speaking of stolen bases, last year I started including a measure that considered only base stealing. Obviously there's a lot more that goes into being a leadoff hitter than simply stealing bases, but it is one of the areas that is often cited as important. So I've included the ranking for what some analysts call net steals, SB - 2*CS. I'm not going to worry about the precise breakeven rate, which is probably closer to 75% than 67%, but is also variable based on situation. The ML and leadoff averages in this case are per team lineup slot:

1. HOU (Bourn/Bourgeois/Schafer), 29

1. NYN (Reyes/Pagan), 29

3. SEA (Suzuki), 26

Leadoff average, 11

ML average, 3

28. CHA (Pierre), -3

29. STL (Theriot/Furcal), -6

29. CLE (Brantley/Sizemore/Carrera), -6

The Indians have been just missed the trailer spots on a number of these lists. At least Cleveland and St. Louis are at the bottom largely because their leadoff hitters didn’t attempt that many steals. Only Milwaukee and Baltimore leadoff hitters (16 and 21 respectively) attempted fewer steals than Cleveland (24) and St. Louis (18). Neither the Tribe (58%) nor the Redbirds (56%) had success when they did steal, but they weren’t trying it all that much. The White Sox, on the other hand, were 31-48 (65%), a poor percentage and the eleventh-most attempts.

Let's shift gears back to quality measures, beginning with one that David Smyth proposed when I first wrote this annual leadoff review. Since the optimal weight for OBA in a x*OBA + SLG metric is generally something like 1.7, David suggested figuring 2*OBA + SLG for leadoff hitters, as a way to give a little extra boost to OBA while not distorting things too much, or even suffering an accuracy decline from standard OPS. Since this is a unitless measure anyway, I multiply it by .7 to approximate the standard OPS scale and call it 2OPS:

1. BOS (Ellsbury), 882

2. NYN (Reyes/Pagan), 835

3. MIL (Weeks/Hart), 834

Leadoff average, 733

ML average, 723

28. CHA (Pierre), 669

29. SF (Torres/Rowand), 645

30. WAS (Bernadina/Desmond/Espinosa), 630

Along the same lines, one can also evaluate leadoff hitters in the same way I'd go about evaluating any hitter, and just use Runs Created per Game with standard weights (this will include SB and CS, which are ignored by 2OPS):

1. BOS (Ellsbury), 6.7

2. NYN (Reyes/Pagan), 6.2

3. TEX (Kinsler), 6.1

Leadoff average, 4.6

ML average, 4.4

28. CHA (Pierre), 3.4

29. SF (Torres/Rowand), 3.4

30. WAS (Bernadina/Desmond/Espinosa), 3.4

Finally, allow me to close with a crude theoretical measure of linear weights supposing that the player always led off an inning (that is, batted in the bases empty, no outs state). There are weights out there (see The Book) for the leadoff slot in its average situation, but this variation is much easier to calculate (although also based on a silly and impossible premise).

The weights I used were based on the 2010 run expectancy table from Baseball Prospectus. Ideally I would have used multiple seasons but this is a seat-of-the-pants metric. Last year’s post went into the detail of how I figured it; this year, I’ll just tell you that the out coefficient was -.22, the CS coefficient was -.587, and for other details refer you to that post. I then restate it per the number of PA for an average leadoff spot (741 in 2011):

1. BOS (Ellsbury), 29

2. TEX (Kinsler), 26

3. NYN (Reyes/Pagan), 25

Leadoff average, 0

ML average, -3

28. CHA (Pierre), -20

29. WAS (Bernadina/Desmond/Espinosa), -20

30. SF (Torres/Rowand), -21

From an overview of all of these metrics, I think it’s safe to say that Red Sox and Mets leadoff hitters were pretty effective while White Sox, Nationals and Giants were not. I was a little disappointed that the Braves and Astros didn’t make any lists together here as each team used both Michael Bourn and Jordan Schafer in twenty or more games out of the #1 spot. Obviously that’s a possibility when players are traded for each other, but it would have been particularly amusing had one team been on the leader list and the other on the trailer list.

A spreadsheet with all of the data and the full lists is available.

Thursday, December 01, 2011

Statistical Meanderings 2011

I have to apologize in advance for this--it sort of resembles a bad Jayson Stark piece with better metrics but less interesting tidbits.

* The discrepancy in R/G between the AL and NL (for the offenses) expanded to .33 (4.46 to 4.13) after a one-year blip that saw the two circuits only .12 runs apart. The leagues were equal in walk rate (.090 and .091 per at bat), but the AL hit for a higher BA (.258 to .253) and with more power (.150 to .139 ISO).

* I certainly do not intend to dispute the notion that Houston was the worst team in baseball, but Minnesota actually had a lower EW% and PW%. Based on runs and runs allowed, Houston “should have” won 61.8 games to Minnesota’s 61.5, and runs created expected a wider gap, 63.3 to 59.8. Obviously this does not consider strength of schedule, but it does put into perspective just how disastrous the Twins’ season was.

* Tampa Bay led the majors in converting balls in plays into outs by a wide margin; their DER of .712 was as far ahead of second place LAA as the Angeles were ahead of twentieth place STL. The Rays also led the majors in modified fielding average, albeit not by a runaway margin.

As a brief aside, “modified” fielding average is no more complex or accurate than regular old fielding average, except I remove strikeouts and assists from the formula. It would actually be easier to work with if I looked at the complement (errors/(putouts less strikeouts + errors)), but fielding average has been expressed that way for ever and it’s not a particularly telling metric in any event.

* In 2010, major league teams had an unusually high W% at home (.559) and 28 teams had a higher W% at home than on the road. This led to some speculation about whether there was something afoot.

2011 did not provide any such conspiracy fodder. Home teams had an abnormally low W% (.526), and only 23/30 teams (77%) won with a greater frequency at home. It was the lowest HW% for MLB since 2001 (.524), and 2005 was the last time that only 23 teams were better at home (only 20 were in 2001).

* The Giants scored 2.91 runs per game at home, the lowest output since 1972. They had to do the near impossible to achieve this by scoring less than the legendary 2010 Mariners (2.95). Offensive ineptitude combined with their good defense resulted in San Francisco playing in the lowest overall scoring context (7.09 RPG) in the majors since the 2003 Dodgers (6.98).

* Don’t tell anyone, but the two teams that struck out the fewest times were the Rangers (930) and the Cardinals (978). Both did unsurprisingly ground into a lot of double plays--Texas was sixth in MLB with 135 and St. Louis’ 169 was sixteen more than second place Baltimore.

* I always like to run a chart showing each playoff team’s RAA broken down by offense and defense:

As you can see, the average playoff team was fairly balanced. The only subpar unit in the group was the defense of the World Champion St. Louis Cardinals.

* At first glance, there was nothing remarkable about the Kansas City bullpen:

Their 4.26 relief eRA was equal to the American League average. But the interesting thing is that all of them were rookies except for Joakim Soria. I’ve already said nice things about Greg Holland in my Rookie of the Year post, so I won’t repeat that here.

* Someone beat me to it, but it is worth pointing out how low Trever Miller’s innings to appearance ratio was, particularly during his time in St. Louis. Miller recorded 47 outs in 39 appearances (1.21 O/G) with the Cards. I cannot state this absolutely, but I believe that is the lowest ratio in ML history for a pitcher with 20 or more appearances. The previous low I can find is Randy Flores with the 2009 Rockies (36 outs/27 games, 1.33). Miller’s complete season line was a yeoman 64 outs in 48 games, tying Flores’ record. A fitting achievement for Tony LaRussa’s final season if I may say so myself.

* One of the stats I track for relievers is inherited runners/game. In an era where leverage index is readily available, it doesn’t yield much marginal value, but I always like looking at closer usage through IR/G. Closers usually dominate the bottom of the IR/G list (I believe Mariano Rivera led full-time AL closers at .31, which was 71st out of 85 relievers), but it’s always fun to see which closers were never brought in with runners on base. If a manager never calls on his closer with runners on, he’s either really locked into bullpen roles, or he really doesn’t trust him. I’d assume the latter was the case with Kevin Gregg, who inherited zero runners in 2011. The former was the case for John Axford (1 in 74 appearances).

* Brian Wilson has taught us that a quirky personality, a ridiculous beard, and a World Series ring can get you a lot of commercials with 7 RAR. Who was the last closer so marginal that got so much publicity?

* Which Yankee reliever is which?

The point here is not to compare the two, but to point out that David Robertson had a really great season.

* You wouldn’t know it from watching the playoffs (and Ron Washington and the Rangers reluctance to use him that eventually turned into an outright dropping off of the roster), but Koji Uehara ranked fifth in RAR among AL relievers and was seventeenth last year. Of course, if all you went by was Washington’s managing, you would be shocked to learn where Nick Punto tends to rank on RAR lists.

* Five major league starters averaged 110 or more pitches per start this year, which has to be the most in some time. I’m pretty sure that hasn’t happened since I’ve been including P/S in my year end stat reports, although I didn’t go back and check to make sure. The five were: Verlander (117), Weaver (113), Halladay (111), Shields (111) and Sabathia (110).

* At the risk of cherry picking (as I’m sure I’m leaving out some pitchers that were talked about similarly but have had continued success, plus one season is obviously insufficient to draw conclusions in any event), I always find it a little satisfying when pitchers that were said to be DIPS beaters have either terrible or high BABIP seasons. Trevor Cahill is in the latter category--he wasn’t horrible by any means, and a .306 BABIP is not that high, but it still is not the kind of season a good DIPS beater should have. JA Happ, on the other hand, was atrocious and gave up an identical .306 BABIP. Even Charlie Morton sort of fits--even looking at his entire season, he wound up at -3 RAA with a .323 BABIP. Along those lines, what are the odds that Josh Tomlin is in the major leagues in five years? They can’t be that good.

* JoJo Reyes seemed to get a lot of attention for his lengthy (by time, especially) losing streak early in the year. Or perhaps my impression of that is off, magnified by the fact that I watched him get his first win pitching against Cleveland. In any event, Reyes may have had some bad luck along the way, but a lot of it evened out in 2011. A pitcher with a 6.45 RRA, 6.24 eRA and 5.21 dRA should consider himself darn lucky to wind up 7-11.

* PSA: David Freese is 28 and ranked 6th in RG among NL third basemen. I overlooked it, but Chase Headley actually had a .393 OBA and created 6.1 runs per game, second to Pablo Sandoval among NL third baseman. So postseaon hardware aside, Padres fans shouldn’t feel too terribly about which of their possible third basemen they actually have.

* AL players with negative RAR who at one time were actually good included Vernon Wells, Magglio Ordonez, JD Drew, Justin Morenau, Alex Rios, Chone Figgins and Adam Dunn. Morneau went from first among AL first baseman in RG in his concussion-shortened 2010 to last in 2011.

* AL players who had an OBA greater than their SLG were: Ryan Sweeney, Chris Getz, JD Drew and Adam Dunn. But for as bad as Dunn’s season was, Chone Figgins’ was actually worse on a rate basis. Figgins only played in 81 games to Dunn’s 122, but still held just a -15 to -17 RAR lead. Figgins created 1.75 runs per game, lowest among all major league players with 300 PA, lower even than Paul Janish (1.90).

* Which of these teammates would you assume was more valuable, based on the statistics presented here?

Of course, any opinion you’d form would be woefully incomplete, because I’ve only given you offensive statistics, without telling you anything about position or defense. Offensively, though, they are nearly indistinguishable. So what if I tell you that one of these players is a slow first baseman and the other one is a center fielder? Surely, the center fielder must have been more valuable, right?

How about these two teammates?

They both play the same position, but one of them was signed as a free agent and took the other’s spot at their common position (third base)--so the one who was pushed off played 105 games at 1B/DH and 55 games at the other infield positions. The one who got the fielding job was more likely the more valuable player, right?

One would think. But the first baseman finished 10th in the MVP voting and the center fielder finished 13th. The third baseman finished fifteenth while the 1B/DH finished 8th and got a first place vote.