The occasionally unreliable and hilarious, impossible statistical lines sometimes seen in Yahoo! box scores have been a recurring feature throughout this blog's history, and here is the 2009 debut. This is not the only box score in which I have noticed this tonight.

Why do I use Yahoo for box scores if there are occasional lapses? I don't have the world's fastest internet connection and Yahoo offers a relatively clean, low bandwidth presentation. The day after the game, though, I use Baseball-Reference.

Monday, April 27, 2009

Great Moments in Yahoo! Box Scores

Monday, April 20, 2009

Keeping Score With Henry Chadwick

One of the many old books available for full download on Google Books is/was Henry Chadwick’s 1874 Chadwick’s Base Ball Manual. (Since I wrote this piece and downloaded the book, the full-text PDF version of the book appears to have disappeared from Google Books, or at least I cannot find it.). The specific edition I have linked was published in London by George Routledge and Sons. As Chadwick explains in the introduction, “The advent of the American base ball players in England bids fair to bring about the introduction of a new game into the extended circle of British sports and pastimes, and one, too, well calculated to achieve a popularity second only to that of the English national game of cricket; and this new field sport is the American game of BASE BALL. Though of English origin, this game is fully entitled to the name of American, and it is a sport just suited to the peculiar temperament of the people of that great republic, as it is full of excitement, occupies but little time, and can be engaged in with equal zest by the youngest schoolboys or by trained professional ball players, to the latter of whom it affords full scope for the exercise of those mental as well as physical attributes which mark the intelligent and cultured athlete.”

In typical Chadwick fashion, these two sentences encompass 149 words. Anyway, the takeaway is that this particular edition of the book was prepared for an English audience in the hopes that baseball would emerge as a major sport in that country. Of course, as we all know, Chadwick’s optimism was unfounded, and baseball has never taken off across the pond, although there devoted British fans certainly do exist.

The portion of the book that I am going to focus on here doesn’t do justice to the work as a whole, but I’ll let you explore that on your own if you are so inclined. Here is a little tease from page 27 as Chadwick describes the role of the “short fielders”:

In the present position of the game there is but one “short-stop”, and he stands to the left of the infield between the second and third base positions. Ultimately, however, a “right-short” will be introduced, which will make the field one of ten men instead of nine, as now.

It is unfair to Mr. Chadwick that I have quoted two passages in which he is 0-2 at predicting on the future of the game (although in this case, ten men and ten innings was something of a personal crusade, and perhaps he hoped that writing a forecast with such confidence would encourage the spread of the ten-man game). My point is not to mock his errors in prognostication, but rather to illustrate what an interesting period piece this is, and what a great window it is into the mind of one of the most influential men in baseball history.

What I want to focus on here is Chadwick’s scoring system. As the premier early baseball writer, Chadwick’s influence was felt far and wide, and so his early system of scorekeeping influenced those that came later, and still influences the standard scorekeeping of today.

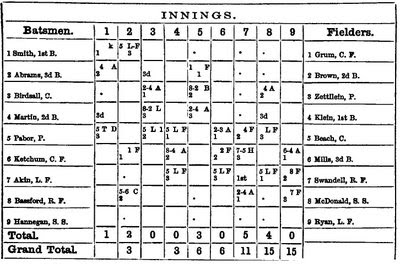

Pages 33-43 of the book discuss Chadwick’s scoring system, and if you are interested I’d encourage you to read them for yourself. I am just going to give a brief summary and reproduce the sample scoresheet that Chadwick includes. This sheet is for the batting of the Unions in their game against the Eckfords of Brooklyn on June 6, 1866:

The most striking similarity to modern scorekeeping is in the general layout of the grid, which for the standard method of scoring has scarcely changed. Nine rows for the batting order, and nine columns for each of the innings in which their performance is recorded. Chadwick reproduces the opposing fielders as well on the far side of the page. While some modern scoresheets (particularly those used by announcers) include the opponents’ fielders for reference purposes, it was pretty much a necessity to have that information at hand if scoring by Chadwick’s system, as we shall see.

What is most strikingly different about Chadwick’s scoring method? The fact that there is no record of how a batter reached base, or how he advanced around the bases takes the cake. As you can verify by checking the runs tally for each inning at the bottom of the page, the solid dots indicate that the player scored a run. For any player that didn’t score a run, there is notation to record how they were retired, or where on the bases they were stranded.

The numbers placed on the extreme left of each scorebox indicate the out number in the course of the inning. So in the first, the “1” in Smith’s box indicates he was the first out; the “2” in Abrams’ that he was the second; and the “3” in Pabor’s that he was the third.

The “k” in Smith’s box indicates that he was a strikeout victim, just as it would today. As Chadwick explains, the letter K [indicates] how [the batter was] put out, K being the last letter of the word “struck.” The letter K is used in this instance as being easier to remember in connection with the word struck than S, the first letter, would be.

This guiding principle in establishing letter codes is further illustrated by Chadwick’s use of “L” for a foul ball (also used undoubtedly because “F” is already reserved for a fly) and “D” for a catch on the bound (in early baseball, catches made on the first bound were fair, and even once the NL had been established there was a period of times in which outs could be recorded on a foul caught on the first bounce). The other important letter codes are “A” for a runner retired at first, “B” for a runner retired at second, “C” for a runner retired at third, “H” for a runner retired at home, “T” for a foul tip, and “R” for a runner put out between bases. Various combinations could be formed form these.

Thus, in the first inning we can see that Abrams was retired at first and that Pabor was retired “T D”--a tip caught on the bound, combining those two codes. But what does the “4” that precedes A indicate in Abrams’ box, and the “5” that preceded T D in Pabor’s?

It means that the fielder who bats fourth in the opposing order made the play on Abrams, and now we see why it was imperative that the opponents’ batting order be reproduced on the page--Chadwick identified fielders by their lineup slot, not by the position numbers we use today. Thus it makes sense that Pabor’s “5” reflects on the catcher of the Eckfords, who we would obviously expect to make the play on a foul tip.

As seen later in the sheet, assisted putouts are recorded in a similar fashion as we still do today. In the fourth, Ketchum was out at first “8-4”, which a glance at the Eckford lineup reveals to be a routine 6-3 in today’s shorthand.

The scoring for runners left on base is straight forward--the “3d” in Martin’s first inning box (or Abrams’ third or Martin’s eighth) simply indicates that he was stranded on third. Likewise, Akin was stranded on first in the seventh, and no Union runner was stranded on second in this contest.

Of note is an oddity that could not be seen in modern baseball, which is that in the third, the Unions’ last batter was Pabor, and he completed his plate appearance by fouling to the catcher (at least as far as I can tell; I’m not exactly sure what the “1” or lower case “l” is supposed to signify). The third out was made by Martin, who apparently was already on base.

Under the rules of the time, it was the man in the lineup who followed the last man retired who would lead off the next inning, not the man in the lineup who followed the last man to complete a plate appearance, and so Pabor led off the fourth…and again fouled to the catcher, although this time the notation clearly indicates it was a foul fly.

While this is all very interesting in its own right for a scorekeeping aficionado like myself, I am now going to launch into a digression about the relationship between Chadwick’s scoring and early statistics. As those of you that have read works like The Hidden Game of Baseball (John Thorn and Pete Palmer) or The Numbers Game (Alan Schwarz) already know, early box scores didn’t contain very much in the way of offensive data. The earliest included just runs and hits, and often contained much more detail on fielding (specifically putouts, assists, and errors).

If one’s only objective in scoring a game was to record runs and outs along with detailed fielding statistics, than the system used in this example by Chadwick makes perfect sense. Why bother recording how a runner reached base, or how many bases his hit was worth, if that information was not going to be recorded for posterity? (However, in the Manual cited here, Chadwick does explain a system for recording that type of information. Interestingly, though, he describes it as a “reporting” system, necessary for “reporting a game for a detailed description in a journal.” In other words, he would include these types of details in his account of the game, but not in the accompanying box score).

The decision to record just runs and outs was not as misguided in its own time as it would be today. It was a different game, then, one in which extra base hits and walks were not terribly common, there was a large number of errors, and a high percentage of batters who reached base wound up scoring (In the case of the Unions for whom Chadwick reproduced a scoresheet, 15 runs were scored with just three stranded. I’m not claiming that was representative of a typical game at the time, but it certainly can serve as a singular data point in that discussion). Knowing just the number of outs a player made and the number of runs he scored told you much more about his real value than such data would today.

Of course, more detailed data was collected in short order, and batting average overtook runs as the most important individual offensive category. In one sense this was obviously a positive development, as it attempted to remove from the batter’s record the influence of his teammates (in another, of course, it was negative as it would enshrine batting average as the number one offensive indicator for a century to come, even when further developments in the game made BA’s alleged superiority even more questionable) . But one thing that was largely lost in the shuffle was the importance of outs as the proper (*) context in which to view offensive performance.

I wonder if or how the development of conventional statistical wisdom would have been altered had the box score column remained “outs” instead of “at bats”. The move to at bats obscured the fact that at bats = outs + hits. By hiding the outs in the broader category of “at bats”, which are easily dismissed as simply a playing time measure, they were hidden from the view of casual fans.

Of course, unless you also consider walks, the result might be the same; valuing hits in relationship to outs is ultimately the same as valuing them in relationship to at bats. But if a hits/outs ratio was used rather than a hits/at bats ratio, there would be many more people who would inherently accept that outs are the proper denominator for an overall offensive rate stat. One of the big steps in converting a lot of people to a sabermetric outlook is to convince them that using outs and not just total opportunities (AB or PA) results in the best model of true offensive value.

People have no trouble accepting innings pitched as the denominator for many pitching statistics, as of course everyone understands that is how ERA is calculated. But mainstream views on pitching statistics also benefit from the fact that innings are thought of as the measure of playing time, despite the fact that batters faced makes more sense from that narrow standpoint.

The average fan thinks about a batter’s playing time in terms of AB or PA, and a pitcher’s in terms of innings. Then when he wants to state the batter’s productivity, he thinks of it terms of AB or PA, while accepting innings for pitchers. My claim is that these two are connected, as those not of a sabermetric bent generally don’t spend much time thinking about these things.

In fairness to casual fans, there is reason to think that the denominator of an overall productivity measure should be different for pitchers and hitters--since the pitcher stands alone, it is obvious to put him in team (outs) context, while a batter is just one of nine. But again, I doubt that many non-sabermetricians have thought too deeply along those lines.

To tie this digression back to Chadwick, I wonder what the conventional wisdom would be today had outs remained prominent in the box score rather than been pushed aside by at bats, and had the relationship between runs and outs remained at the center of batting statistics.

(*) At least close enough. I know as well as anybody that there are other approaches like RAA/PA and R+/PA and R+/O+ and the list goes on, so don’t leave any anonymous comments on this point.

Monday, April 13, 2009

Snowflakes

As I write this in February, I look out my window and see snow covering the ground. I cannot off the top of my head recall the last time I looked outside and did not see a blanket of snow on the ground. Snow is characteristic of winter, which is the one season in which baseball has no place, at least not too far north of the Tropic of Cancer. And snow is a form of precipitation, and precipitation, regardless of the season or which form it takes, is the natural enemy of baseball.

So why on earth am I writing a piece entitled “snowflakes” on a baseball blog? Good question, lame answer forthcoming. It’s a metaphor (or is it a simile?(*)), and it’s not even my own.

Let me quote Stew Thornley from his article “In the Braves’ Clubhouse”, part of SABR’s The Fenway Project:

"To me, a completed scoresheet is a work of art. It’s not the person entering the hieroglyphics who is the artist; rather it is the players on the field, creating the events that are then recorded. At the end of the game, the scorer has a unique piece of art, as individual as a snowflake or a fingerprint, no two games ever being the same."

Thornley is of course correct that no two games are the same, and is also correct that it is the players on the field and not the scorekeeper that truly matter. However, it is also true that each individual scorer's system is unique. There are no two people who keep score EXACTLY the same way (with one potential exception which I’ll discuss below). Even if two individuals use the exact same scoring codes and symbols, there will be some individuality in the scoresheet. Perhaps you record the attendance, or who performed the national anthem, or jot down a note in the margin that a given pitch was a curveball.

The snowflake metaphor also works in the sense that most scoresheets are easily recognizable as such from afar, but truly reveal their uniqueness up close. Most scoring systems have a lot in common; most people use the standard 1-9 numbers to identify fielders, for instance. More esoteric systems can generally be cracked without much trouble assuming you know what events the symbols and codes must be representing.

The potential exception to the rule of uniqueness I alluded to above is that of formulaic systems like Project Scoresheet that have a code for just about everything. A distinction must be drawn between the Project Scoresheet style of scoring and the complete system itself. There is very little room for individuality in a system in which just about every event imaginable has been accounted for. On the other hand, one can use the PS-style of three lines to describe the action of each PA while retaining their own personal approach.

I don’t mean this as a criticism of the Project Scoresheet system. For the efficient entry of game accounts into computer systems, standardization is a wonderful thing. Certainly a lot of thought (from a lot of very smart people, including Craig Wright) went into the development of that system, and to the extent that you could objectively measure the efficiency of a scoring method, it would likely score very well. On the other hand, if you want to read back a game without the aid of a computer, it would score poorly, as I’ve discussed before.

Of course, Project Scoresheet was designed by people with eyes on detailed data collection, and thus is sensible even if a little excessive. What if you had a system developed by bureaucrats from an international sports governing body, obsessed not only with standardization but also with mind-numbing uniformity, a dash of political correctness, and more concern with just being able to produce a box score from the finished product than its usefulness in developing a play-by-play log? Well, you’d probably end up with the monstrosity that is the International Baseball Federation (IBAF) scoring manual (available for download from the website of the Great Britain Baseball Scorers Association here).

125 pages of details on minutiae, reminders that "Any reference in this IBAF Scoring Rules to 'he', 'him' or 'his' shall be deemed to be a reference to 'she',

'her' or 'hers' as the case may be when the person is a female", instructions for perforating and attaching a new scoresheet in the case of insufficient space (no joke--see page 21), repetitive notations of substitutions, and a very run-of-the-mill "trace the diamond" approach are the highlights of this earth-shattering treatise on scorekeeping. This is a case where you really have to see it to believe it.

Strict adherence to someone else’s system of scoring may be a necessity in some cases, but it can suck the life out of the activity. With the easy access to data through scoreboards and internet game trackers and the like, the only good reason for anyone to keep score in a non-official capacity today is because the individual finds it enjoyable. And as is the case with so many things in life, it is much more likely that what you find enjoyable will be what comes naturally to you or what you develop yourself over time, rather than a bunch of rules, regulations, and procedures handed to you by an "expert".

If you don’t keep score and would like to try, don’t feel compelled to adopt any particular approach. Learn a little bit about a number of different approaches and figure out which elements of each appeal to you. Figure out through trial and error what works for you and what doesn’t, and always try to record the details that you really feel are important.

Don’t make your scoresheet another flake in the big pile I’m looking at right now. Make it a unique snowflake that your five year-old self might have caught on his glove and admired.

(*) I really should look up the distinction between the two, but I'm lazy about things like that. I seem to recall being told that metaphors were of the form "A is B" and similes were "A is like B". And then there is the category of analogies, which just muddies things up a bit more. All of this serves to illustrate why I always liked math class better than English. As does the first and last paragraphs of the body of the post.

Sunday, April 05, 2009

2009 Predictions

I write a predictions post every year; it is one of my favorite posts to write and simultaneously one of my least favorite to write. I like it because it is offered completely in the spirit of fun, and there is no need to take any pains to make sure I have the proper coefficient on triples; I dislike it because sometimes it’s impossible to convince people to take an activity of this type in that spirit.

I guide my predictions with a freely available set of projections (usually Marcel) and some very simple assumptions about which players each team will run out on the field, and equally simple assumptions about how to project the outs and innings that are not used up by the regulars. In other words, it’s not completely from the seat of my pants, but it’s not particularly involved. So is there any reason why you should care about what I say? No, none whatsoever, especially since I only use those estimates as a guide.

The other thing I always like to point out is that the team I pick to win is not necessarily one I expect to win. I have picked the Indians to win the AL Central, but if I had to make an even money bet on whether they would make the playoffs or not, I’d take "no". But if you feel the Indians have a 35% chance to win, the Tigers 25%, the Twins 20%, the White Sox 15%, and the Royals 5% (numbers for illustration only), who are you going to pick to win if you can only pick one? The one with a 35% chance, of course, even though that means there’s a 65% they won’t win the division.

"No plan ever survives the first encounter with the enemy", right? Same is true for team predictions. Teams ditch a deadweight you expected them to carry (or do the opposite), key players get hurt, a few individuals on a team manage to have career years, a team makes a huge deadline trade, and all of a sudden you look smart when maybe you shouldn’t have (like when I picked the Dodgers in the NL West last year), or dumb when you couldn’t have known a whole lot better (me and just about everyone else on the face of the earth picked the Yankees to make the playoffs, although by picking them to win it all perhaps I went a bit too far). You’ll also notice that I tend to be fairly conservative in my predictions, sticking largely with teams that had success last year; some of that is due to being guided by a conservative projection system, but some of it is just my nature.

When I get down to predictions for the awards, and who will win the pennant, that’s even more of a crapshoot. So if you want my one sentence opinions on each big league team, and promise not to get upset at what you see, read on. If you don’t, or can’t agree to the second part, please read someone else’s predictions. There are hundreds of sources for much more serious examinations than this.

AL EAST

1. Boston

2. New York (wildcard)

3. Tampa Bay

4. Toronto

5. Baltimore

Just as was the case last year, I have the Yankees and Red Sox almost exactly equal on paper. Last year I claimed that I believed the Red Sox had better depth in case of injuries, then proceeded to pick New York to win it anyway. I won’t make that mistake this year (and thus the Yanks will probably win). The Rays are going to disappoint a lot of people this year, I’m afraid. It’s usually a mistake to believe that a team that already won 90+ games has a strong chance to improve even if they are young, and it’s a common mistake. Could the Rays make the playoffs again? Of course; I think they should contend, but my guess would be they fall short. My quick and dirty numbers peg Tampa as the third best team in the AL, but unfortunately the other two are right here as well. The Blue Jays missed a golden opportunity last year as they got brilliant pitching and a Bronx crackup, but their offense was not up to the challenge. They’ve not done much to address it, and now that pitching staff looks like a shadow of itself. The Orioles should be better, and they’re actually starting to collect some interesting talent, but this division is not forgiving.

AL CENTRAL

1. Cleveland

2. Detroit

3. Chicago

4. Minnesota

5. Kansas City

My track record at picking the AL Central is dreadful. The easiest explanation is that it has been a very volatile division, with three winners in three years, plus a very strong wildcard in 2006. Only the Royals have come into the last few seasons without any believers on their side. The other possible explanation is that since my team is in this division, try as I might to analyze it objectively and downplay my fandom, it throws me off.

That may be the case this year as I think the Indians are the strongest team in the division. As I’ve discussed already, I’m not crazy about this team, and I feel they are a weak favorite, but they are my choice. I really don’t see a lot of room between Cleveland and Detroit, and really not a whole lot between the Tribe and Twinkies either. The Tigers are a team that I expect to be overlooked. After all, 2008 was supposed to be their year, with many picking them to win the pennant, and some people tend to get gunshy when they get burned by a prediction. However, I think their pitching is bound to improve and their offense is still a threat. The White Sox are the team I love to hate in MLB at the moment (*), and I have to admit that was the determining factor in a coin flip between them and the Twins. The team I’ve picked to finish fourth in the AL Central has a remarkable tendency to end up winning it. But really, they have taken a step backwards this offseason. I haven’t checked formally, but it sure seems like the Twins might have been the most inactive team in the game. I think this is a big mistake (from a win-now perspective, at least) as they scored many more runs in 2008 than their components indicated they should have. If they’re banking on that again, good luck to ‘em. The Royals went out and added key pieces like Mike Jacobs, Kyle Farnsworth, and Willie Bloomquist, so expect me to look like a fool come October. Seriously, though, some are touting them as "this year’s Rays", and I just don’t see it. For one thing, it’s silly to look for "this year’s Rays", as turnarounds like that are quite rare, which is why they are such a big deal when they occur. And while those aforementioned acquisitions (well, mostly Jacobs and Coco Crisp) are being cited by some as a key factor in the expected surge, I don’t think that much of them. If this team is going to take a great leap forward, a lot of it will need to come from their holdovers. Billy Butler and Alex Gordon could very well take big steps, but I still don’t think it would be enough to win the division as weak as it may look on paper.

(*) I have no inherent dislike for any major league team, with the sometime exceptions of the Tigers depending on how many UM hats I see in the crowd when they are on TV. I happen to be unable to stomach Ozzie Guillen (for a litany of reasons which I’ll spare you), and the treatment of Nick Swisher last year only intensified my disdain for the man. It’s sort of chic among a certain element of the stathead crowd to bash Kenny Williams too despite the ChiSox’ recent success; not wanting to appear petty, I simply blame him for agreeing to work with Ozzie. In the early part of the decade, I used to pull for the White Sox in the annual White Sox/Twins pseudo-playoff race. Honest.

AL WEST

1. Los Angeles

2. Oakland

3. Seattle

4. Texas

The Angels are in a place where I almost feel compelled to pick against them, even if I do think they have the best shot at the division, just to be a contrarian. But none of the other three teams are particularly inspiring either, and LA gets brownie points from me for acquiring a player I really like (Bobby Abreu) in place of one I have disliked for many years (Garrett Anderson, and nothing personal). Apparently Billy Beane thinks the A’s have a shot (or just felt Matt Holliday was being offered for a song), and far be it from me to tell him he’s nuts. It’s not that hard to construct a scenario in which Oakland contends--Eric Chavez is reasonably healthy and productive, Trevor Cahill and/or Brett Anderson step in as rotation pieces, Brad Ziegler remains dominant--but I can’t justify picking them over the Halos. Seattle has always been a team I loved to hate, but my early impressions of the Zduriencik regime are positive, and if you openly hire Tom Tango as a consultant, you can’t be all bad, right? The Rangers are my pick for worst AL team. They lost Milton Bradley, I’m still not completely sold on Josh Hamilton and Ian Kinsler at their 2008 levels, and their pitching is the same as it ever was.

NL EAST

1. New York

2. Atlanta (wildcard)

3. Philadelphia

4. Florida

5. Washington

The National League offseason mystified me. Maybe this is a sign that I am stupid, and should quit attempting to figure this stuff out, and stick to writing about esoteric sabermetric topics. For the sake of making this interesting, I’ll take the tack that it truly was mystifying. Omar Minaya acted like a post-game radio caller who only remembers the last thing he saw, working on upgrading the bullpen while letting a rotation stay fairly thin and apparently ignoring offense in the corner outfield spots. That aside, the Mets’ core of stars (Beltran, Reyes, Santana, Wright) is the most impressive in all of baseball (yes, I’d take them over Jeter-Rodriguez-Sabathia-Teixiera, although who wouldn’t love to have either), and having Francisco Rodriguez and JJ Putz is not a bad thing. Atlanta used to be the team I picked against just because, but last year I picked them to win and they collapsed. Frank Wren addressed their rotation weakness adequately in the offseason, and if they could ever stay healthy, Gonzalez and Soriano would be a scary left-right bullpen punch. Unfortunately, the Braves have apparently concluded that outfield offense is not important, or that they are content to wait for Jones, Heyward, and Schaefer. Continuing the theme of NL head-scratchers, the Phillies somehow decided it was a good idea to give up a first-round draft pick to downgrade in left field, at a higher price and longer contract to an older player than their incumbent got, while adding yet another left-handed bat to the lineup. My numbers say the Phillies are still the logical wildcard pick, but if you want to go by the numbers, go see what PECOTA or CHONE or the like have to say--they're starting from a better base anyway. I really don’t want to pick the Marlins fourth, but they’ve made me look dumb before, and they have some intriguing young talent. The Nationals are finally free from Jim Bowden, and while climbing soapboxes isn’t really my thing, I find the associated scandals more distasteful many times over than any steroid revelations.

NL CENTRAL

1. Chicago

2. St. Louis

3. Milwaukee

4. Cincinnati

5. Houston

6. Pittsburgh

I hate this division. No, not the teams, but the inherent unfairness of having to beat five teams instead of three or four. This is what happens when you switch to three divisions with expansion on the horizon. Maybe you should have thought about that, Bud and co.? What would be so bad about having two divisions with two wildcards? Or, gasp, no divisions and four playoff qualifiers? In fairness, the long-term trend in all pro sports is for more divisions, not less, but that doesn’t make it any dumber.

Rant aside (although I have a longer version already written up for a dry spell of post ideas--with probabilities!), the Cubs join the NL "What were they thinking?" list. What was the point of trading Mark DeRosa and the last year of his contract to install Aaron Miles at second? Why Mr. Hendry did you make Jake Peavy your white whale? What on earth did you gain by trading Ronny Cedeno and Garret Olson for Aaron Heilman? Petty quibbles aside, the Cubs are clearly the best team in this division on paper, and I think they rival the Mets for league-wide honors. Last year I was way too pessimistic about the Cardinals; this may be overcompensation, and their pitching still scares me, but the other clubs have taken a step back. The Brewers could stay in the mix, if Gallardo and Parra can step up, as their offense remains solid if unspectacular. The Reds are squandering some decent talent on the notion (not solely, but it paints the picture) that a group consisting of Willy Taveras, Chris Dickerson, Jacque Jones, Norris Hopper, Jonny Gomes, and Laynce Nix is capable of filling one outfield spot, let alone two. If everything goes right the Astros could be a fringy contender type again, but those odds aren’t good. With the Steelers’ Super Bowl win, I’ve seen a little of the meme that the Steelers and Pirates illustrate the difference between the NFL and MLB vis-à-vis small market competitiveness. Sure. Let the Steelers draft like the Bengals for fifteen years and see how many Super Bowls they win.

NL WEST

1. Los Angeles

2. Arizona

3. San Francisco

4. Colorado

5. San Diego

The Dodgers finally let their young guys play last year (except Andy LaRoche, who I still hold out some hope for but also can’t blame LA for pushing aside), and it paid off. They still weren’t any sort of juggernaut, and I do believe this division has improved, but I give them a slight edge. I bit my tongue last year when the Diamondbacks started hot and were hailed as baseball’s best team, which means I can’t gloat too much about what ended up happening. A lot of people came up with a lot of reasons as to why the Pythagorean record was wrong, but to the extent that the next season’s results can reflect (which admittedly is not as great as it is sometimes made out to be), it wasn’t. Yet they have too much young-ish talent to be written off, and I was tempted to pick them to edge out LA. I love how Eric Byrnes’ awful contract led to the awful, but reasonable under the circumstances decision to not offer arbitration to Adam Dunn. The Giants have assembled a pretty impressive rotation, yet they insist on bringing a popgun to the shootout. The Rockies are retreating back to "most boring team in baseball" status, but the 2007 pennant will preclude that from being official for at least a couple more years. I think the Orioles have inherited the mantle; maybe the Royals or Pirates, but they are a little too inept at times to qualify. There aren’t a whole lot of good things to say about the 2009 edition of the Padres, but I respect the organization a great deal so I’ll refrain from snark. And I don’t think they’re as bad as the mainstream consensus seems to think they are.

WORLD SERIES

Boston over New York (N)

In ’07 I picked the BoSox in the East and as world champs (the one time in my life I was actually correct); in ’08 I switched to the Yankees, and the alternating years plan will continue here.

AL Rookie of the Year: C Matt Wieters, BAL

Yes, I know he’s starting in AAA. See Longoria, Evan.

AL Cy Young: Daisuke Matsuzaka, BOS

I think I may have picked him last year. Cut the walk rate, please.

AL MVP: CF Grady Sizemore, CLE

I was going to pick ARod just as an "In your face, drug warriors!" pick, but the injury takes that possibility from infinitesimal to zero. Eventually Grady will luck into a .300 average and the rest of the world will realize that he’s a tremendous ballplayer.

NL Rookie of the Year: OF Colby Rasmus, STL

NL Cy Young: Ubaldo Jimenez, COL

It’s boring to pick Sabathia and Santana and company all the time. My Cy Young picks mostly just reflect my skepticism of the "WBC ruins pitchers!" heme.

NY MVP: 3B David Wright, NYN

He should have one already; I’m going to keep picking him until he gets it.

First manager fired: Dave Trembley, BAL

Best pennant race: AL East if you like good teams, AL Central if you prefer trainwrecks

Worst pennant race: NL Central

Worst teams in each league: Texas, Pittsburgh

Most likely to go .500 in each league: Oakland, Milwaukee

Teams most likely to disappoint (mainstream consensus*): Minnesota, Florida

Teams most likely to surprise (mainstream consensus): Detroit, Atlanta

Best free agent value (among big names): Bobby Abreu, LAA

Worst free agent value (among big names): Raul Ibanez, PHI

Will the Neanderthal League finally win the All-Star game?: flip a coin

Will Neanderthal League partisans extol the moral purity of pitchers hitting?: Not THAT much--only on every last day of interleague play

Will Jake Peavy be traded?: No

Most obnoxious stories of the year: anything involving ARod or steroids will lap the field as usual; complaints about slow starts by WBC participants will also be in contention

Over/under on in-season blog posts: 20--I've managed to build up a decent backlog of posts that aren’t time sensitive, so most weeks should see something posted in this space

(*) I used the predictions from three preview magazines (Lindy’s, Athlon Sports, and The Sporting News) to define maninstream consensus. Those publications all pick Minnesota to win the AL Central; pick Florida second (wildcard), third, and fourth respectively; pick Detroit third, fifth, and fifth respectively; and pick Atlanta fourth, fourth, and third respectively.