The National League seemed to be in great shape entering 1881 after another fairly uneventful off-season; other than the expulsion of

The customary annual rule changes were important. The maximums were lowered to seven balls and three strikes. Batting order had to be set prior to the game (previously, the manager could determine the order during the first pass through the lineup. Cap Anson was purportedly a practitioner of this strategy, choosing to bat himself in the first inning should there be runners on base but holding himself back if there were not). Most importantly, though, the pitching box was moved back five feet, from forty-five to fifty.

The pennant race was another breeze for

On June 25, George Gore of

On September 29, the league blacklisted ten players for “confirmed dissipation and general insubordination”. They were Lew Brown (Providence), Ed Caskin (Troy), Bill Crowley (Boston), Buttercup Dickerson (Worcester), Mike Dorgan (Worcester), John Fox (Boston), Emil Gross (Providence), Sadie Houck (Detroit), The Only Nolan (Cleveland), and Lip Pike (Worcester). This wound up marking the end of the major league careers of exactly zero of these men.

The next day, a new standard player contract was approved. It enabled fines for any conduct considered “detrimental to the team”; it also provided no salary protection for injuries or coverage for medical treatment. With the strong-arm tactics against players (new contracts, blacklisting, and the reserve clause), the NL was engendering a fair degree of anti-management sentiment among its players. This would help set the stage for the tumultuous events of the next few years.

One of those events were efforts to establish a new challenger to the NL, one that would address the lack of league teams in major cities like New York, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, and St. Louis.

While all eight NL franchises returned for 1882, the baseball scene they would encounter in 1882 was different than any they had seen before. Their leader would be dead and their strongest rival would be in business.

STANDINGS

As David Nemec points out, 1881 was the most balanced season for the NL in the nineteenth century. Only 23 games separated top from bottom, only 15 games separated second from the cellar, and no team played under .390 ball.

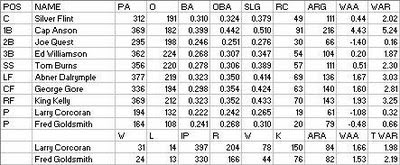

In 1881, the league hit .260/.290/.338, for a .120 SEC, with 5.10 runs and 23.94 outs per game. The fielding average once again reached a new high, this time .905.

It is of course impossible to quantify the exact effect of moving the pitcher’s box back, but it certainly seemed to increase offensive output. Batting average was up 2%, isolated power was up 5%, while walk rate spiked, although only to 4.2% of plate appearances (a 93% increase from 1880). Runs/game were up 8.7%, and strikeouts as a percentage of PA dropped from 8% to 7%.

CHICAGO

“If it’s not broke, why fix it” could well have been the motto for the defending pennant winners, as all regulars returned in their same positions. The team lost ground in terms of dominance but was still heads and shoulders above the best of the league.

Silver

The Grays declined by five games but also found themselves six games closer to first place, although still well behind at nine games back. Catcher Barney Gilligan from

Rookie third baseman Jerry Denny was the first significant player from

Fellow rookie Hoss Radbourn (not yet known as Hoss, one would assume, but things would get awfully confusing if I didn’t refer to players as they are known today) was actually the Grays’ most effective pitcher. He had played in six games as a position player for

There was quite bit of boardroom intrigue surrounding the franchise this season. In August, the shareholders were angry over a projected loss of $1,500 and perceived soft treatment of players (this audacious behavior included paying the salaries of injured players). The board was overhauled, and manager Jack Farrell was replaced by Tom York as manager.

The Bisons see-sawed their way back to the level of their inaugural 1879 NL campaign, in which they finished third, ten games back with a 46-32 record. This year, they went 45-38, ten and a half back and in third place. The 24-58 1880 season certainly appeared to be the outlier.

Curry Foley also came over from

O’Rourke’s nickname was “Orator Jim”--this was due to his loquaciousness. There are numerous anecdotes about O’Rourke’s vocabulary and his willingness to unleash it in everyday use. One deals directly with this season; according to

“I’m sorry, but the exigencies of the occasion and the condition of our exchequer will not permit anything of the sort at this period of our existence. Subsequent developments in the field of finance may remove the present gloom and we may emerge into a condition where we may see fit to reply in the affirmative to your exceedingly modest request.”

Wouldn’t he have at least said “I deeply regret” instead of the simple “I’m sorry”? What kind of purported wordsmith was this guy anyway?

The Wolverines acquitted themselves nicely, finishing in the first division and narrowly missing the .500 mark at 41-43. A reported profit of $12,000 also bode well for the newcomers.

The team was largely composed of NL veterans; only first baseman Martin Powell and pitcher George Derby were true rookies among the regulars.

The Trojans kept most of their team in place and essentially treaded water with a slight decline in the win column. Roger Connor was moved to first base, and his vacant third base position was filled by Frank Hankinson of

The Trojans continued to struggle at the gate, drawing just twelve fans for a September 27 game against

The Reds were unable to pull out of their funk, holding sixth place and falling a game and a half in the standings. On July 2, the proud franchise fell into last place for the very first time.

Pop Snyder returned after not playing in 1880; Ross Barnes did the same, having last been a Red. This would be his swan song, and he acquitted himself quite nicely. Joe Hornung and Bill Crowley moved over from

The Reds had their own pair of rookie starters, perhaps trying to emulate the success of

Whitney’s sobriquet was due to his appearance; Bill James quotes an unnamed reporter as writing that “[Whitney had] a head about the size of a wart with the forehead slanting at an angle of 45 degrees.”

The Harry Wright era ended after the season, as he followed the same trail younger brother George had, departing the Reds for

CLEVELAND

The Blues were unable to hold their gains of 1880, dropping back to seventh place. Mike McGeary was made starting third baseman and manager, but quit after eleven games. He was replaced by John Clapp, who came over from

The Only Nolan also made his triumphant return to the NL after last pitching for another team called the Blues (

WORCESTER

The Brown Stockings finished last, but as mentioned above, the NL was pretty balanced. At .390, they had the highest W% yet for a last-place team, and a record good enough to have finished ahead of two teams in 1880 and three in 1879. The team added Hick Carpenter from

Dorgan started out as the manager, but his play was hampered by a sore arm in June and then was relieved of his duties in August, to be replaced by Harry Stovey. Lee Richmond asked for his release in June, but was brought back in August, then closed the season by purportedly getting into a beanball war with

Some of the Brown Stockings became suspicious of outfielder Lip Pike (5 games) when he made three errors in one game; he was suspended and later blacklisted. The Brown Stockings also saw Dorgan and Buttercup Dickerson placed on the list. The latter did not help his cause when he told manager/front office man Freeman Brown that he would stop drinking. Brown asked “When does the good work start?”, to which Dickerson replied “As soon as they shut down the distilleries.” (Nemec, pg. 138)

Here is a link to the leaders/trailers and all-star post.

No comments:

Post a Comment

I reserve the right to reject any comment for any reason.