For some reason this winter I was struck with nostalgia for 1994 Topps, and decided that it would be a good off-season project to collect the complete set. I’d never collected a complete current set when I was interested in cards – I didn’t have the resources, and I preferred to get a variety of different sets (although as I said, 1994 Topps was my favorite based on how represented it was among my cards) or to buy Ken Griffey cards. Yes, my year of baseball card obsession corresponded with thinking that Ken Griffey was the best and coolest player. Not that I have anything against Griffey, but in retrospect, it now seems like a lot of wasted time and money that could have been spent on Barry Bonds or Rickey Henderson cards. Within a year I was getting seriously into statistics and discovering that Bonds, not Griffey, was the best player in baseball, but by then I wasn’t buying a lot of cards.

I say I never collected a complete “current” set because I do in fact have a complete set of 1991 Donruss, or extremely close to it. They are ugly cards, to be sure, but we used to buy boxes of them dirt cheap at Big Lots. I also have to be pretty close on 1990 and 1992 Topps, although I never sat down and tried to inventory what I had.

Of course it would have been easier and cheaper to just buy the complete set, especially for Topps, but I decided it would be more fun to start with my old collection, buy some unopened packs, and buy singles to fill in whatever gaps were left. So that’s what I did, and it was more fun and more expensive. I felt conflicted about opening previously sealed boxes of twenty-six year old cards; on the one hand, it felt like squandering the last of a non-renewable resource. On the other, these poor cards had been stuck inside for two and a half decades. Time for them to get out and be admired like they were made for.

There was a complication, though. I believe 1994 Topps was the first Topps set to be glossed on both sides, and they get stuck together. I was usually able to get them apart without too much damage, but there were a handful of unfortunate incidents, although I think Mike Mussina was the biggest name for which I ended up with a severely defaced card. At least by 1994 there was no disgusting gum enclosed.

There were frustrations -- I ended up with a lot of extras, naturally, but not as many of some of the cards that I now consider most desirable (Barry Bonds, Rickey Henderson, Roger Clemens, Jeff Bagwell) as I would have liked. As always seems to be the case, Alan Trammell and Lou Whitaker stuck together – I got zero of the former and only one of the latter. There were amusing coincidences as well. In one pack I got a Lee Smith and a Trevor Hoffman back-to-back – the man who contemporaneously held the career saves record, and the man who would break it. When I was opening a pack during commercials while watching the Super Bowl, I pulled a Pat Mahomes card.

One thing that struck me as I was putting the set together was that these were “my” cards, but not “my” players. 1994 Topps is and always will be the consummate ideal of a baseball card in my mind, but of course they represent the players of the 1993 season, in which I cared zilch about baseball. The 1995 or 1996 set would much better capture the universe of baseball players as I came to love it, but the cards themselves would not hold the same nostalgia value.

The other thing that struck me after I had mostly completed the set in the spring was how the baseball experience of 1994 would reverberate to that of 2020, the only two seasons of my time as a fan that have been catastrophically shortened (144 games in 1995 sounds real good right about now).

With that, I will write about the cards themselves. On the back, the second picture takes up about a quarter of the card, but leaves plenty of room for a statistical record that is probably better than what was published in contemporary Who’s Who In Baseball. You get the demographics (height/weight, bats/throws, draft status, how acquired by current team, DOB/birthplace, and current home), plus decent stats for the entirety of the player’s major league career (and if you don’t believe that, look at how they had to squeeze it in on Nolan Ryan’s final card). For pitchers, the statistical categories are G, IP, W, L, R, ER, SO, BB, GS, CG, SHO, SV, and ERA – weird order, but total runs allowed? Can’t argue with that. For hitters: G, AB, R, H, 2B, 3B, HR, RBI, SB, SLG, BB, SO, AVG. For 1994, that’s pretty good.

The set is not marred by inserts – there are a number of “special” cards, but none that are inserts – they all are standard numbered, not irritants designed to make it impossible to complete a set. Unfortunately, these special cards are the weakness of the set.

1. 1993 Draft Picks

At first, this should make you excited, because the #1 overall pick in 1993 was the greatest player ever to be taken #1 overall, and one of the greatest to be drafted period, Alex Rodriguez. But he is nowhere to be seen, nor are most of the other best players drafted in the first round (Brian Anderson, Chris Carpenter, Darren Dreifort, Torii Hunter, Derrek Lee, Trot Nixon, Jason Varitek), with Billy Wagner being the exception. The highest draft pick represented is Wayne Gomes (#4). I assume that since the draft picks weren’t MLBPA members, they were able to cut their own deals, which explains why they’re absent, but it’s still a disappointing lot, and there are about 35 cards wasted on them.

2. Prospects

These cards feature four players to a card, which means you get only a tiny picture of their faces. It’s typically one player from AAA, AA, A, and a draftee. There’s one card for each position, and it’s worth listing them out:

C (#686): Chris Howard, Carlos Delgado, Jason Kendall, Paul Bako

1B (#448): Greg Pirkl, Roberto Petagine, DJ Boston, Shawn Wooten

2B (#527): Norberto Martin, Ruben Santana, Jason Hardtke, Chris Sexton

3B (#369): Luis Ortiz, David Bell, Jason Giambi, George Arias

SS (#158): Orlando Miller, Brandon Wilson, Derek Jeter, Mike Neal

OF (#79): Billy Masse, Stanton Cameron, Tim Clark, Craig McClure

OF (#237): Curtis Pride, Shawn Green, Mark Sweeney, Eddie Davis

OF (#616): Eddie Zambrano, Glen Murray, Chad Mottola, Jermaine Allensworth

SP (#316): Chad Ogea, Duff Brumley, Terrell Wade, Chris Michalak

RP (#713): Todd Williams, Ron Watson, Kirk Bullinger, Mike Welch

Similar to the draft picks, I’m not sure how many players the powers that were at Topps at actually had the ability to choose for these cards. That being said, if this is the success rate, why bother? This did produce the first Topps card for Derek Jeter (I’m not going to wade through the excruciating minutia to try to figure out if it qualifies as his Rookie card or not), but sharing a card with the likes of Brandon Wilson and Mike Neal is not the stuff 1952 Topps Mickey Mantles are made out of. I’d say they hit a homer run with catcher, and the rest of these are just sad. How could you pick twelve outfielders and only have Shawn Green to show for it? And I for one am shocked that the relief pitcher prospects didn’t pan out.

3. Coming Attractions

These cards, the last 28 regular cards in the set (minus the Series 2 checklists that close it out; 4 of the 792 cards are devoted to checklists), feature two prospects from each team. These guys were all supposed to be close to the majors, and so there are more familiar names; I’m not going to list them all, but I’ll give you the top names to give you a flavor. Excluded from this list are the two Braves, arguably the two best players in the group on the same card, a definite success – Chipper Jones (the best player represented by leaps and bounds) and Ryan Klesko.

Carl Everett, Bob Hamelin, Scott Hatteberg, Raul Mondesi, Troy O’Neal, Bill Pulsipher, Steve Trachsel, Rondell White

4. Future Stars

These cards are sprinkled in, one for each team, showing a player pretty close to the majors. There are a couple big names, and as a kid this was my favorite card in the set (along with Ken Griffey, of course). I had multiple copies, and I also happened to pull a bunch of them when opening old packs:

Unfortunately, I don’t consider the design of these to be so cool anymore, with the “futuristic” border. The pixelization of everything in the background of the shot other than the player is not a horrible idea, but as an adult I’d just prefer a nice picture. The future stars were:

Paul Carey (BAL)

Frank Rodriguez (BOS)

Justin Thompson (DET)

Domingo Jean (NYA)

Alex Gonzalez (TOR)

Scott Ruffcorn (CHA)

Manny Ramirez (CLE)

Billy Brewer (KC)

Jose Valentin (MIL)

Rich Becker (MIN)

Garrett Anderson (CAL)

Eric Helfand (OAK)

Tim Davis (SEA)

Benji Gil (TEX)

Javy Lopez (ATL)

Nigel Wilson (FLA)

Cliff Floyd (MON)

Butch Huskey (NYN)

Tony Longmire (PHI)

Matt Walbeck (CHN)

Calvin Reese (CIN) (yes, the back of the card does mention “Pokey”)

Todd Jones (HOU)

Danny Miceli (PIT)

Tripp Cromer (STL)

Mark Thompson (COL)

Billy Ashley (LA)

Ray McDavid (SD)

Salomon Torres (SF)

The weirdest thing for me about grouping 1994 teams by division is the Tigers in the AL East.

5. 1993 Topps All-Stars

Apparently these are Topps’ own picks for 1994 All-Stars in each league. They appear in a run to close out the first series (at least until the checklists gum things up). The design of the cards is unremarkable, but what’s more interesting are the stats on the back – they split the players’ stats by pre- and post-All Star Break, even though they are full season selections, and the stats are different – they show Total Bases and OBP, but not SLG which are on the regular cards. Who knew it was easier to pick all-stars than prospects?

C: Mike Piazza, Mike Stanley

1B: Fred McGriff, Frank Thomas

2B: Robbie Thompson, Roberto Alomar

3B: Matt Williams, Wade Boggs

SS: Jeff Blauser, Cal Ripken

LF: Barry Bonds, Albert Belle

CF: Lenny Dykstra, Ken Griffey

RF: David Justice, Juan Gonzalez

SP: Greg Maddux, Jack McDowell

RP: Randy Myers, Jeff Montgomery

6. Measures of Greatness

These feature one active player of historical stature and compare their statistics to those of the average Hall of Famer and one particular Hall of Famer at their position (this statistical comparison is shown in Bill James’ seasonal notation, per about 158 games, which I assume was chosen since it's the average of 154 and 162). The pairings can be entertaining, though:

C: Darren Daulton/Roy Campanella

In fairness, this wasn’t a great time for great catchers – Carlton Fisk and Gary Carter had retired, Mike Piazza and Ivan Rodriguez were too young for this kind of company. This did not age well.

1B: Frank Thomas/Jimmie Foxx

2B: Ryne Sandberg/Rogers Hornsby

3B: Wade Boggs/Brooks Robinson

I’d make fun of this one, but there was still an extreme dearth of HOF third baseman at this point; Mike Schmidt wasn’t in the Hall yet and George Brett had just retired. Eddie Mathews is not a good comp for Wade Boggs at the plate stylistically, so the pickings are slim. There still hasn’t been a third baseman who really comps to Boggs.

SS: Cal Ripken/Luis Aparicio

Same problem, although Ernie Banks would be a much better fit than Aparicio. Here's the back of the card as an example of these:

OF: Barry Bonds/Willie Mays

This comparison looks even better now than it did then.

OF: Ken Griffey/Stan Musial

This is a bad comp (Mays would be the lazy one), or at least would be a bad comp were it not for the fact that both hail from Donora, Pennsylvania. Does the card point this out? Nope.

OF: Kirby Puckett/Joe DiMaggio

Really? Not Duke Snider or something?

DH: Paul Molitor/Roberto Clemente

I’ll cut them some slack since Molitor was multi-positional and closing in on 3,000 hits. Oddly, pitchers were omitted from Measures of Greatness.

Wednesday, August 19, 2020

1994 Topps, pt. 2

Wednesday, August 05, 2020

1994 Topps, pt. 1

If you asked me today what about baseball interested me most (besides the basics like which team is going to win the World Series or how the Indians are going to do this season), I would say “sabermetrics and scorekeeping”. That answer has probably been the same since 1996 or so. If you’d asked me in 1995 I would have said “statistics” rather than sabermetrics, and scorekeeping wasn’t on the radar. But if you’d asked me in 1994, statistics would have been second, but a fairly distant second. The answer would have been “baseball cards”.

I was always interested in facts and figures, so it’s no surprise that when I became an overnight baseball fanatic, I was caught up in lists of pennant winners and ERA leaders and the like, and this led me down a path to sabermetrics. I think my early fascination with baseball cards comes from already having collected football and basketball cards (which in turn came from an innate desire to collect things), so it was natural for interest in a sport to be followed closely by an interest in cards. Of course, just as is the case for statistics, baseball is the sport for card collecting, or at least certainly was circa 1994.

I am not a historian of baseball cards, so take the discussion that follows with a grain of salt. It’s written by the seat of my pants, and I could have done so much more accurately when I was nine. But 1994 seems to represent the zenith of the roller coaster history of card manufacturers that took the hobby from a Topps monopoly to five major players and eventually right back to a Topps monopoly. In 1994, the five majors were cranking out multiple sets, aimed at different levels of consumer. In retrospect it seems like an obvious bubble, in the way that bubbles usually do but only after the fact. Who was the audience truly demanding a super-premium card set?

Yet most of the majors had a base set (Topps, Fleer, Donruss, Upper Deck, Score); a premium set (Topps Stadium Club, Fleer Ultra, Leaf, Upper Deck SP, Pinnacle); a super-premium set (Topps Finest, Fleer Flair, Leaf Limited); plus the other sets which included Donruss’ Triple Play and Studio, Topps’ Bowman, and Upper Deck Collector’s Choice. The strike would help deal a blow to the insanity, but it seems like a market that was already ripe for a correction.

I try to actively avoid thinking that baseball or anything else peaked when I first fell in love with it, as so many people do. But I will always maintain that 1994 had the best cards (not that I know anything about post-1995 cards), the perfect combination of an increase in production values (gloss on both sides, although I will have more to say on that later) but when you could still collect a base set loaded with commons without a million insert cards. And aesthetically? They were (mostly) beauties.

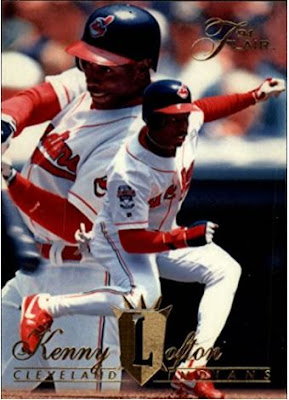

Super-premium cards were inherently ridiculous, but I don’t think any looked better than 1994 Fleer Flair with its regal names and thick stock:

On the premium side, all of the offerings from the majors were memorable. Topps Stadium Club was the worst, but there’s something delightfully 90s about the names on the front of the card, with the lower case first name and the all caps surname straight out of the labelmaker your dad had stashed away in the basement. Although we’re not going to talk about what the backs of these cards looked like:

Upper Deck always put out a classy card (although I will admit that these rank well behind the debut set from 1989 and the iconic Ken Griffey rookie card):

Yet Pinnacle topped them:

Fleer Ultra was better still:

And 1994 Leaf was a work of art:

I contend the base sets were even better designed (for what they were) in 1994. Since I didn’t have a whole lot of disposable income, almost all of my pack purchases were of these five sets. Comparing the number of each I appear to have in my collection, I can roughly assume that my order in preference working from least-favorite to favorite was:

5. Donruss

This one was (and remains) a distant fifth on my order of preference, even though I think it’s a very nice-looking card. I have roughly equal amounts of the next three:

4. Upper Deck Collector’s Choice

I think it’s the pinstripes that really makes these pop. Plus the old-timey drawing to go along with the player’s position.

3. Fleer

The only flaw is that the player’s name is understated by being wrapped in small letters around the team’s logo.

2. Score

Sadly, what made this set great is what makes them less desirable to collect twenty-six years later. I was not in anyway part of the “cards in the bike spokes” generation. I treated my cards, particularly the cards of stars, as if they were my most valuable possession (in fact, they probably WERE my most valuable possession). And yet I’m not sure I came across one in my album that didn’t have obvious chipping to those amazing dark borders.

As you’ve probably guessed from the title of this post, Topps is #1.

After 1994, it was all downhill for baseball cards, at least for the rest of the nineties when I was still interested in them although no longer obsessed. What went wrong? The most personal is that I became much more interested in the numbers on the back of the cards than in the cards themselves. But the biggest problem is that the crisp designs of 1994, which focused on the player pictures and used borders, names, and logos to complement them, were benched in favor of drawing attention to everything but the picture. Perhaps the designers wanted to show off what they could do in MS Paint (and some really do look like they were designed in MS Paint)? Or maybe they decided that since everyone had nice pictures on their cards, it was necessary to seek a graphic design that would differentiate them from the pack (pun intended)?

Perhaps we should have seen it coming, as Topps juxtaposed their beautiful 1994 base set with the questionable Stadium Club and the horrifying Topps Finest:

When looking at 1995, I think it’s instructive to look at what happened to the base sets, which were all so great in 1994. In 1995, worst went to first by default – Donruss changed it up a little bit, while their competitors decided to jump off a cliff together:

If I remember correctly, before the strike was settled, Upper Deck leaped first in the spring with a “special edition” of Collector’s Choice. Out are the classic pinstripes; in is garish blue. In is haphazard capitalization. Out were my dollars:

Score may have realized that the black borders were a disaster for the long-term condition of their cards; I’m not sure why that required shrinking the pictures, adding a faux wood/dark green border, and circles of varying sizes for some unknown reason. What’s sad here is that they were so close to some classic baseball motifs – wood grain can work (see 1987 Topps), but it helps if it looks like what you’d see on a bat. Green is the color I most associate with baseball – but the green of the grass, not a pine tree.

People didn’t say “hold my beer” in 1995, but if they did, Topps would have, going from the most perfect set ever printed to a terrible font in gold (so much for the first and classiest parallel set, Topps Gold), often hard to read because it brushes up against the border which for some reason is not straight:

Still, nothing better captures the 1995 self-own of the big five than the monstrosity that was 1995 Fleer. 1994 Fleer, as I said above, was gorgeous but almost too simple. They fixed that right quick. In 1995, Fleer decided that they would obscure the front of the card with all of the biographical info that no one cared about (and often didn’t believe). But that wasn’t enough – they decided that each of the six divisions should have a unique design. None got it worse than the AL Central, which was not good news for the cards of my Indians heroes:

Perhaps all of the card designers were on strike in solidarity with the players? I think 1995 was a low point – it got a little better later in the decade. But even the bible of the hobby lost its way. When I was taken by cards, I naturally asked for a subscription to Beckett Baseball Card Monthly. I’ll always remember the cover of the first issue I bought separately – a great portrait of Jeff Bagwell. These frameable covers would persist beyond 1994, but not too much longer, and eventually even Beckett covers would have headlines everywhere, like 1995 Fleer had grown beyond the borders of its set and conquered all things baseball card.