The spreadsheets are published as Google Spreadsheets, which you can download in Excel format by changing the extension in the address from "=html" to "=xls". That way you can download them and manipulate things however you see fit.

The data comes from a number of different sources. Most of the basic data comes from Doug's Stats, which is a very handy site, or Baseball-Reference. KJOK's park database provided some of the data used in the park factors, but for recent seasons park data comes from B-R. Data on inherited/bequeathed runners comes from Baseball Prospectus.

The basic philosophy behind these stats is to use the simplest methods that have acceptable accuracy. Of course, "acceptable" is in the eye of the beholder, namely me. I use Pythagenpat not because other run/win converters, like a constant RPW or a fixed exponent are not accurate enough for this purpose, but because it's mine and it would be kind of odd if I didn't use it.

If I seem to be a stickler for purity in my critiques of others' methods, I'd contend it is usually in a theoretical sense, not an input sense. So when I exclude hit batters, I'm not saying that hit batters are worthless or that they *should* be ignored; it's just easier not to mess with them and not that much less accurate.

I also don't really have a problem with people using sub-standard methods (say, Basic RC) as long as they acknowledge that they are sub-standard. If someone pretends that Basic RC doesn't undervalue walks or cause problems when applied to extreme individuals, I'll call them on it; if they explain its shortcomings but use it regardless, I accept that. Take these last three paragraphs as my acknowledgment that some of the statistics displayed here have shortcomings as well, and I've at least attempted to describe some of them in the discussion below.

The League spreadsheet is pretty straightforward--it includes league totals and averages for a number of categories, most or all of which are explained at appropriate junctures throughout this piece. The advent of interleague play has created two different sets of league totals--one for the offense of league teams and one for the defense of league teams. Before interleague play, these two were identical. I do not present both sets of totals (you can figure the defensive ones yourself from the team spreadsheet, if you desire), just those for the offenses. The exception is for the defense-specific statistics, like innings pitched and quality starts. The figures for those categories in the league report are for the defenses of the league's teams. However, I do include each league's breakdown of basic pitching stats between starters and relievers (denoted by "s" or "r" prefixes), and so summing those will yield the totals from the pitching side. The one abbreviation you might not recognize is "N"--this is the league average of runs/game for one team, and it will pop up again.

The Team spreadsheet focuses on overall team performance--wins, losses, runs scored, runs allowed. The columns included are: Park Factor (PF), Home Run Park Factor (PFhr), Winning Percentage (W%), Expected W% (EW%), Predicted W% (PW%), wins, losses, runs, runs allowed, Runs Created (RC), Runs Created Allowed (RCA), Home Winning Percentage (HW%), Road Winning Percentage (RW%) [exactly what they sound like--W% at home and on the road], Runs/Game (R/G), Runs Allowed/Game (RA/G), Runs Created/Game (RCG), Runs Created Allowed/Game (RCAG), and Runs Per Game (the average number of runs scored an allowed per game). Ideally, I would use outs as the denominator, but for teams, outs and games are so closely related that I don’t think it’s worth the extra effort.

The runs and Runs Created figures are unadjusted, but the per-game averages are park-adjusted, except for RPG which is also raw. Runs Created and Runs Created Allowed are both based on a simple Base Runs formula. The formula is:

A = H + W - HR - CS

B = (2TB - H - 4HR + .05W + 1.5SB)*.76

C = AB - H

D = HR

Naturally, A*B/(B + C) + D.

I have explained the methodology used to figure the PFs before, but the cliff’s notes version is that they are based on five years of data when applicable, include both runs scored and allowed, and they are regressed towards average (PF = 1), with the amount of regression varying based on the number of years of data used. There are factors for both runs and home runs. The initial PF (not shown) is:

iPF = (H*T/(R*(T - 1) + H) + 1)/2

where H = RPG in home games, R = RPG in road games, T = # teams in league (14 for AL and 16 for NL). Then the iPF is converted to the PF by taking x*iPF + (1-x), where x = .6 if one year of data is used, .7 for 2, .8 for 3, and .9 for 4+.

It is important to note, since there always seems to be confusion about this, that these park factors already incorporate the fact that the average player plays 50% on the road and 50% at home. That is what the adding one and dividing by 2 in the iPF is all about. So if I list Fenway Park with a 1.02 PF, that means that it actually increases RPG by 4%.

In the calculation of the PFs, I did not get picky and take out “home” games that were actually at neutral sites.

There are also Team Offense and Defense spreadsheets. These include the following categories:

Team offense: Plate Appearances, Batting Average (BA), On Base Average (OBA), Slugging Average (SLG), Secondary Average (SEC), Walks and Hit Batters per At Bat (WAB), Isolated Power (SLG - BA), R/G at home (hR/G), and R/G on the road (rR/G) BA, OBA, SLG, WAB, and ISO are park-adjusted by dividing by the square root of park factor (or the equivalent; WAB = (OBA - BA)/(1 - OBA), ISO = SLG - BA, and SEC = WAB + ISO).

Team defense: Innings Pitched, BA, OBA, SLG, Innings per Start (IP/S), Starter's eRA (seRA), Reliever's eRA (reRA), Quality Start Percentage (QS%), RA/G at home (hRA/G), RA/G on the road (rRA/G), Battery Mishap Rate (BMR), Modified Fielding Average (mFA), and Defensive Efficiency Record (DER). BA, OBA, and SLG are park-adjusted by dividing by the square root of PF; seRA and reRA are divided by PF.

The three fielding metrics I've included are limited it only to metrics that a) I can calculate myself and b) are based on the basic available data, not specialized PBP data. The three metrics are explained in this post, but here are quick descriptions of each:

1) BMR--wild pitches and passed balls per 100 baserunners = (WP + PB)/(H + W - HR)*100

2) mFA--fielding average removing strikeouts and assists = (PO - K)/(PO - K + E)

3) DER--the Bill James classic, using only the PA-based estimate of plays made. Based on a suggestion by Terpsfan101, I've tweaked the error coefficient. Plays Made = PA - K - H - W - HR - HB - .64E and DER = PM/(PM + H - HR + .64E)

Next are the individual player reports. I defined a starting pitcher as one with 15 or more starts. All other pitchers are eligible to be included as a reliever. If a pitcher has 40 appearances, then they are included. Additionally, if a pitcher has 50 innings and less than 50% of his appearances are starts, he is also included as a reliever (this allows some swingmen type pitchers who wouldn’t meet either the minimum start or appearance standards to get in).

For all of the player reports, ages are based on simply subtracting their year of birth from 2015. I realize that this is not compatible with how ages are usually listed and so “Age 27” doesn’t necessarily correspond to age 27 as I list it, but it makes everything a heckuva lot easier, and I am more interested in comparing the ages of the players to their contemporaries than fitting them into historical studies, and for the former application it makes very little difference. The "R" category records rookie status with a "R" for rookies and a blank for everyone else; I've trusted Baseball Prospectus on this. Also, all players are counted as being on the team with whom they played/pitched (IP or PA as appropriate) the most.

For relievers, the categories listed are: Games, Innings Pitched, estimated Plate Appearances (PA), Run Average (RA), Relief Run Average (RRA), Earned Run Average (ERA), Estimated Run Average (eRA), DIPS Run Average (dRA), Strikeouts per Game (KG), Walks per Game (WG), Guess-Future (G-F), Inherited Runners per Game (IR/G), Batting Average on Balls in Play (%H), Runs Above Average (RAA), and Runs Above Replacement (RAR).

IR/G is per relief appearance (G - GS); it is an interesting thing to look at, I think, in lieu of actual leverage data. You can see which closers come in with runners on base, and which are used nearly exclusively to start innings. Of course, you can’t infer too much; there are bad relievers who come in with a lot of people on base, not because they are being used in high leverage situations, but because they are long men being used in low-leverage situations already out of hand.

For starting pitchers, the columns are: Wins, Losses, Innings Pitched, Estimated Plate Appearances (PA), RA, RRA, ERA, eRA, dRA, KG, WG, G-F, %H, Pitches/Start (P/S), Quality Start Percentage (QS%), RAA, and RAR. RA and ERA you know--R*9/IP or ER*9/IP, park-adjusted by dividing by PF. The formulas for eRA and dRA are based on the same Base Runs equation and they estimate RA, not ERA.

* eRA is based on the actual results allowed by the pitcher (hits, doubles, home runs, walks, strikeouts, etc.). It is park-adjusted by dividing by PF.

* dRA is the classic DIPS-style RA, assuming that the pitcher allows a league average %H, and that his hits in play have a league-average S/D/T split. It is park-adjusted by dividing by PF.

The formula for eRA is:

A = H + W - HR

B = (2*TB - H - 4*HR + .05*W)*.78

C = AB - H = K + (3*IP - K)*x (where x is figured as described below for PA estimation and is typically around .93) = PA (from below) - H - W

eRA = (A*B/(B + C) + HR)*9/IP

To figure dRA, you first need the estimate of PA described below. Then you calculate W, K, and HR per PA (call these %W, %K, and %HR). Percentage of balls in play (BIP%) = 1 - %W - %K - %HR. This is used to calculate the DIPS-friendly estimate of %H (H per PA) as e%H = Lg%H*BIP%.

Now everything has a common denominator of PA, so we can plug into Base Runs:

A = e%H + %W

B = (2*(z*e%H + 4*%HR) - e%H - 5*%HR + .05*%W)*.78

C = 1 - e%H - %W - %HR

cRA = (A*B/(B + C) + %HR)/C*a

z is the league average of total bases per non-HR hit (TB - 4*HR)/(H - HR), and a is the league average of (AB - H) per game.

In the past I presented a couple of batted ball RA estimates. I’ve removed these, not just because batted ball data exhibits questionable reliability but because these metrics were complicated to figure, required me to collate the batted ball data, and were not personally useful to me. I figure these stats for my own enjoyment and have in some form or another going back to 1997. I share them here only because I would do it anyway, so if I’m not interested in certain categories, there’s no reason to keep presenting them.

Instead, I’m showing strikeout and walk rate, both expressed as per game. By game I mean not nine innings but rather the league average of PA/G. I have always been a proponent of using PA and not IP as the denominator for non-run pitching rates, and now the use of per PA rates is widespread. Usually these are expressed as K/PA and W/PA, or equivalently, percentage of PA with a strikeout or walk. I don’t believe that any site publishes these as K and W per equivalent game as I am here. This is not better than K%--it’s simply applying a scalar multiplier. I like it because it generally follows the same scale as the familiar K/9.

To facilitate this, I’ve finally corrected a flaw in the formula I use to estimate plate appearances for pitchers. Previously, I’ve done it the lazy way by not splitting strikeouts out from other outs. I am now using this formula to estimate PA (where PA = AB + W):

PA = K + (3*IP - K)*x + H + W

Where x = league average of (AB - H - K)/(3*IP - K)

Then KG = K*Lg(PA/G) and WG = W*Lg(PA/G).

G-F is a junk stat, included here out of habit because I've been including it for years. It was intended to give a quick read of a pitcher's expected performance in the next season, based on eRA and strikeout rate. Although the numbers vaguely resemble RAs, it's actually unitless. As a rule of thumb, anything under four is pretty good for a starter. G-F = 4.46 + .095(eRA) - .113(K*9/IP). It is a junk stat. JUNK STAT JUNK STAT JUNK STAT. Got it?

%H is BABIP, more or less--%H = (H - HR)/(PA - HR - K - W), where PA was estimated above. Pitches/Start includes all appearances, so I've counted relief appearances as one-half of a start (P/S = Pitches/(.5*G + .5*GS). QS% is just QS/(G - GS); I don't think it's particularly useful, but Doug's Stats include QS so I include it.

I've used a stat called Relief Run Average (RRA) in the past, based on Sky Andrecheck's article in the August 1999 By the Numbers; that one only used inherited runners, but I've revised it to include bequeathed runners as well, making it equally applicable to starters and relievers. I use RRA as the building block for baselined value estimates for all pitchers. I explained RRA in this article, but the bottom line formulas are:

BRSV = BRS - BR*i*sqrt(PF)

IRSV = IR*i*sqrt(PF) - IRS

RRA = ((R - (BRSV + IRSV))*9/IP)/PF

The two baselined stats are Runs Above Average (RAA) and Runs Above Replacement (RAR). This year I've revised RAA to use a slightly different baseline for starters and relievers as described here. The adjustment is based on patterns from the last several seasons of league average starter and reliever eRA. Thus it does not adjust for any advantages relief pitchers enjoy that are not reflected in their component statistics. This could include runs allowed scoring rules that benefit relievers (although the use of RRA should help even the scales in this regard, at least compared to raw RA) and the talent advantage of starting pitchers. The RAR baselines do attempt to take the latter into account, and so the difference in starter and reliever RAR will be more stark than the difference in RAA.

RAA (relievers) = (.951*LgRA - RRA)*IP/9

RAA (starters) = (1.025*LgRA - RRA)*IP/9

RAR (relievers) = (1.11*LgRA - RRA)*IP/9

RAR (starters) = (1.28*LgRA - RRA)*IP/9

All players with 250 or more plate appearances (official, total plate appearances) are included in the Hitters spreadsheets (along with some players close to the cutoff point who I was interested in). Each is assigned one position, the one at which they appeared in the most games. The statistics presented are: Games played (G), Plate Appearances (PA), Outs (O), Batting Average (BA), On Base Average (OBA), Slugging Average (SLG), Secondary Average (SEC), Runs Created (RC), Runs Created per Game (RG), Speed Score (SS), Hitting Runs Above Average (HRAA), Runs Above Average (RAA), Hitting Runs Above Replacement (HRAR), and Runs Above Replacement (RAR).

Starting in 2015, I'm including hit batters in all related categories for hitters, so PA is now equal to AB + W+ HB. Outs are AB - H + CS. BA and SLG you know, but remember that without SF, OBA is just (H + W + HB)/(AB + W + HB). Secondary Average = (TB - H + W + HB)/AB = SLG - BA + (OBA - BA)/(1 - OBA). I have not included net steals as many people (and Bill James himself) do, but I have included HB which some do not.

BA, OBA, and SLG are park-adjusted by dividing by the square root of PF. This is an approximation, of course, but I'm satisfied that it works well (I plan to post a couple articles on this some time during the offseason). The goal here is to adjust for the win value of offensive events, not to quantify the exact park effect on the given rate. I use the BA/OBA/SLG-based formula to figure SEC, so it is park-adjusted as well.

Runs Created is actually Paul Johnson's ERP, more or less. Ideally, I would use a custom linear weights formula for the given league, but ERP is just so darn simple and close to the mark that it’s hard to pass up. I still use the term “RC” partially as a homage to Bill James (seriously, I really like and respect him even if I’ve said negative things about RC and Win Shares), and also because it is just a good term. I like the thought put in your head when you hear “creating” a run better than “producing”, “manufacturing”, “generating”, etc. to say nothing of names like “equivalent” or “extrapolated” runs. None of that is said to put down the creators of those methods--there just aren’t a lot of good, unique names available.

For 2015, I've refined the formula a little bit (see this post for more) to:

1. include hit batters at a value equal to that of a walk

2. value intentional walks at just half the value of a regular walk

3. recalibrate the multiplier based on the last ten major league seasons (2005-2014)

This revised RC = (TB + .8H + W + HB - .5IW + .7SB - CS - .3AB)*.310

RC is park adjusted by dividing by PF, making all of the value stats that follow park adjusted as well. RG, the Runs Created per Game rate, is RC/O*25.5. I do not believe that outs are the proper denominator for an individual rate stat, but I also do not believe that the distortions caused are that bad. (I still intend to finish my rate stat series and discuss all of the options in excruciating detail, but alas you’ll have to take my word for it now).

Several years ago I switched from using my own "Speed Unit" to a version of Bill James' Speed Score; of course, Speed Unit was inspired by Speed Score. I only use four of James' categories in figuring Speed Score. I actually like the construct of Speed Unit better as it was based on z-scores in the various categories (and amazingly a couple other sabermetricians did as well), but trying to keep the estimates of standard deviation for each of the categories appropriate was more trouble than it was worth.

Speed Score is the average of four components, which I'll call a, b, c, and d:

a = ((SB + 3)/(SB + CS + 7) - .4)*20

b = sqrt((SB + CS)/(S + W))*14.3

c = ((R - HR)/(H + W - HR) - .1)*25

d = T/(AB - HR - K)*450

James actually uses a sliding scale for the triples component, but it strikes me as needlessly complex and so I've streamlined it. He looks at two years of data, which makes sense for a gauge that is attempting to capture talent and not performance, but using multiple years of data would be contradictory to the guiding principles behind this set of reports (namely, simplicity. Or laziness. You're pick.) I also changed some of his division to mathematically equivalent multiplications.

There are a whopping four categories that compare to a baseline; two for average, two for replacement. Hitting RAA compares to a league average hitter; it is in the vein of Pete Palmer’s Batting Runs. RAA compares to an average hitter at the player’s primary position. Hitting RAR compares to a “replacement level” hitter; RAR compares to a replacement level hitter at the player’s primary position. The formulas are:

HRAA = (RG - N)*O/25.5

RAA = (RG - N*PADJ)*O/25.5

HRAR = (RG - .73*N)*O/25.5

RAR = (RG - .73*N*PADJ)*O/25.5

PADJ is the position adjustment, and it is based on 2002-2011 offensive data. For catchers it is .89; for 1B/DH, 1.17; for 2B, .97; for 3B, 1.03; for SS, .93; for LF/RF, 1.13; and for CF, 1.02. I had been using the 1992-2001 data as a basis for some time, but finally updated for 2012. I’m a little hesitant about this update, as the middle infield positions are the biggest movers (higher positional adjustments, meaning less positional credit). I have no qualms for second base, but the shortstop PADJ is out of line with the other position adjustments widely in use and feels a bit high to me. But there are some decent points to be made in favor of offensive adjustments, and I’ll have a bit more on this topic in general below.

That was the mechanics of the calculations; now I'll twist myself into knots trying to justify them. If you only care about the how and not the why, stop reading now.

The first thing that should be covered is the philosophical position behind the statistics posted here. They fall on the continuum of ability and value in what I have called "performance". Performance is a technical-sounding way of saying "Whatever arbitrary combination of ability and value I prefer".

With respect to park adjustments, I am not interested in how any particular player is affected, so there is no separate adjustment for lefties and righties for instance. The park factor is an attempt to determine how the park affects run scoring rates, and thus the win value of runs.

I apply the park factor directly to the player's statistics, but it could also be applied to the league context. The advantage to doing it my way is that it allows you to compare the component statistics (like Runs Created or OBA) on a park-adjusted basis. The drawback is that it creates a new theoretical universe, one in which all parks are equal, rather than leaving the player grounded in the actual context in which he played and evaluating how that context (and not the player's statistics) was altered by the park.

The good news is that the two approaches are essentially equivalent; in fact, they are precisely equivalent if you assume that the Runs Per Win factor is equal to the RPG. Suppose that we have a player in an extreme park (PF = 1.15, approximately like Coors Field pre-humidor) who has an 8 RG before adjusting for park, while making 350 outs in a 4.5 N league. The first method of park adjustment, the one I use, converts his value into a neutral park, so his RG is now 8/1.15 = 6.957. We can now compare him directly to the league average:

RAA = (6.957 - 4.5)*350/25.5 = +33.72

The second method would be to adjust the league context. If N = 4.5, then the average player in this park will create 4.5*1.15 = 5.175 runs. Now, to figure RAA, we can use the unadjusted RG of 8:

RAA = (8 - 5.175)*350/25.5 = +38.77

These are not the same, as you can obviously see. The reason for this is that they take place in two different contexts. The first figure is in a 9 RPG (2*4.5) context; the second figure is in a 10.35 RPG (2*4.5*1.15) context. Runs have different values in different contexts; that is why we have RPW converters in the first place. If we convert to WAA (using RPW = RPG, which is only an approximation, so it's usually not as tidy as it appears below), then we have:

WAA = 33.72/9 = +3.75

WAA = 38.77/10.35 = +3.75

Once you convert to wins, the two approaches are equivalent. The other nice thing about the first approach is that once you park-adjust, everyone in the league is in the same context, and you can dispense with the need for converting to wins at all. You still might want to convert to wins, and you'll need to do so if you are comparing the 2015 players to players from other league-seasons (including between the AL and NL in the same year), but if you are only looking to compare Jose Bautista to Miguel Cabrera, it's not necessary. WAR is somewhat ubiquitous now, but personally I prefer runs when possible--why mess with decimal points if you don't have to?

The park factors used to adjust player stats here are run-based. Thus, they make no effort to project what a player "would have done" in a neutral park, or account for the difference effects parks have on specific events (walks, home runs, BA) or types of players. They simply account for the difference in run environment that is caused by the park (as best I can measure it). As such, they don't evaluate a player within the actual run context of his team's games; they attempt to restate the player's performance as an equivalent performance in a neutral park.

I suppose I should also justify the use of sqrt(PF) for adjusting component statistics. The classic defense given for this approach relies on basic Runs Created--runs are proportional to OBA*SLG, and OBA*SLG/PF = OBA/sqrt(PF)*SLG/sqrt(PF). While RC may be an antiquated tool, you will find that the square root adjustment is fairly compatible with linear weights or Base Runs as well. I am not going to take the space to demonstrate this claim here, but I will some time in the future.

Many value figures published around the sabersphere adjust for the difference in quality level between the AL and NL. I don't, but this is a thorny area where there is no right or wrong answer as far as I'm concerned. I also do not make an adjustment in the league averages for the fact that the overall NL averages include pitcher batting and the AL does not (not quite true in the era of interleague play, but you get my drift).

The difference between the leagues may not be precisely calculable, and it certainly is not constant, but it is real. If the average player in the AL is better than the average player in the NL, it is perfectly reasonable to expect the average AL player to have more RAR than the average NL player, and that will not happen without some type of adjustment. On the other hand, if you are only interested in evaluating a player relative to his own league, such an adjustment is not necessarily welcome.

The league argument only applies cleanly to metrics baselined to average. Since replacement level compares the given player to a theoretical player that can be acquired on the cheap, the same pool of potential replacement players should by definition be available to the teams of each league. One could argue that if the two leagues don't have equal talent at the major league level, they might not have equal access to replacement level talent--except such an argument is at odds with the notion that replacement level represents talent that is truly "freely available".

So it's hard to justify the approach I take, which is to set replacement level relative to the average runs scored in each league, with no adjustment for the difference in the leagues. The best justification is that it's simple and it treats each league as its own universe, even if in reality they are connected.

The replacement levels I have used here are very much in line with the values used by other sabermetricians. This is based both on my own "research", my interpretation of other's people research, and a desire to not stray from consensus and make the values unhelpful to the majority of people who may encounter them.

Replacement level is certainly not settled science. There is always going to be room to disagree on what the baseline should be. Even if you agree it should be "replacement level", any estimate of where it should be set is just that--an estimate. Average is clean and fairly straightforward, even if its utility is questionable; replacement level is inherently messy. So I offer the average baseline as well.

For position players, replacement level is set at 73% of the positional average RG (since there's a history of discussing replacement level in terms of winning percentages, this is roughly equivalent to .350). For starting pitchers, it is set at 128% of the league average RA (.380), and for relievers it is set at 111% (.450).

I am still using an analytical structure that makes the comparison to replacement level for a position player by applying it to his hitting statistics. This is the approach taken by Keith Woolner in VORP (and some other earlier replacement level implementations), but the newer metrics (among them Rally and Fangraphs' WAR) handle replacement level by subtracting a set number of runs from the player's total runs above average in a number of different areas (batting, fielding, baserunning, positional value, etc.), which for lack of a better term I will call the subtraction approach.

The offensive positional adjustment makes the inherent assumption that the average player at each position is equally valuable. I think that this is close to being true, but it is not quite true. The ideal approach would be to use a defensive positional adjustment, since the real difference between a first baseman and a shortstop is their defensive value. When you bat, all runs count the same, whether you create them as a first baseman or as a shortstop.

That being said, using "replacement hitter at position" does not cause too many distortions. It is not theoretically correct, but it is practically powerful. For one thing, most players, even those at key defensive positions, are chosen first and foremost for their offense. Empirical research by Keith Woolner has shown that the replacement level hitting performance is about the same for every position, relative to the positional average.

Figuring what the defensive positional adjustment should be, though, is easier said than done. Therefore, I use the offensive positional adjustment. So if you want to criticize that choice, or criticize the numbers that result, be my guest. But do not claim that I am holding this up as the correct analytical structure. I am holding it up as the most simple and straightforward structure that conforms to reality reasonably well, and because while the numbers may be flawed, they are at least based on an objective formula that I can figure myself. If you feel comfortable with some other assumptions, please feel free to ignore mine.

That still does not justify the use of HRAR--hitting runs above replacement--which compares each hitter, regardless of position, to 73% of the league average. Basically, this is just a way to give an overall measure of offensive production without regard for position with a low baseline. It doesn't have any real baseball meaning.

A player who creates runs at 90% of the league average could be above-average (if he's a shortstop or catcher, or a great fielder at a less important fielding position), or sub-replacement level (DHs that create 3.5 runs per game are not valuable properties). Every player is chosen because his total value, both hitting and fielding, is sufficient to justify his inclusion on the team. HRAR fails even if you try to justify it with a thought experiment about a world in which defense doesn't matter, because in that case the absolute replacement level (in terms of RG, without accounting for the league average) would be much higher than it is currently.

The specific positional adjustments I use are based on 2002-2011 data. I stick with them because I have not seen compelling evidence of a change in the degree of difficulty or scarcity between the positions between now and then, and because I think they are fairly reasonable. The positions for which they diverge the most from the defensive position adjustments in common use are 2B, 3B, and CF. Second base is considered a premium position by the offensive PADJ (.97), while third base and center field have similar adjustments in the opposite direction (1.03 and 1.02).

Another flaw is that the PADJ is applied to the overall league average RG, which is artificially low for the NL because of pitcher's batting. When using the actual league average runs/game, it's tough to just remove pitchers--any adjustment would be an estimate. If you use the league total of runs created instead, it is a much easier fix.

One other note on this topic is that since the offensive PADJ is a stand-in for average defensive value by position, ideally it would be applied by tying it to defensive playing time. I have done it by outs, though.

The reason I have taken this flawed path is because 1) it ties the position adjustment directly into the RAR formula rather than leaving it as something to subtract on the outside and more importantly 2) there’s no straightforward way to do it. The best would be to use defensive innings--set the full-time player to X defensive innings, figure how Derek Jeter’s innings compared to X, and adjust his PADJ accordingly. Games in the field or games played are dicey because they can cause distortion for defensive replacements. Plate Appearances avoid the problem that outs have of being highly related to player quality, but they still carry the illogic of basing it on offensive playing time. And of course the differences here are going to be fairly small (a few runs). That is not to say that this way is preferable, but it’s not horrible either, at least as far as I can tell.

To compare this approach to the subtraction approach, start by assuming that a replacement level shortstop would create .86*.73*4.5 = 2.825 RG (or would perform at an overall level of equivalent value to being an average fielder at shortstop while creating 2.825 runs per game). Suppose that we are comparing two shortstops, each of whom compiled 600 PA and played an equal number of defensive games and innings (and thus would have the same positional adjustment using the subtraction approach). Alpha made 380 outs and Bravo made 410 outs, and each ranked as dead-on average in the field.

The difference in overall RAR between the two using the subtraction approach would be equal to the difference between their offensive RAA compared to the league average. Assuming the league average is 4.5 runs, and that both Alpha and Bravo created 75 runs, their offensive RAAs are:

Alpha = (75*25.5/380 - 4.5)*380/25.5 = +7.94

Similarly, Bravo is at +2.65, and so the difference between them will be 5.29 RAR.

Using the flawed approach, Alpha's RAR will be:

(75*25.5/380 - 4.5*.73*.86)*380/25.5 = +32.90

Bravo's RAR will be +29.58, a difference of 3.32 RAR, which is two runs off of the difference using the subtraction approach.

The downside to using PA is that you really need to consider park effects if you do, whereas outs allow you to sidestep park effects. Outs are constant; plate appearances are linked to OBA. Thus, they not only depend on the offensive context (including park factor), but also on the quality of one's team. Of course, attempting to adjust for team PA differences opens a huge can of worms which is not really relevant; for now, the point is that using outs for individual players causes distortions, sometimes trivial and sometimes bothersome, but almost always makes one's life easier.

I do not include fielding (or baserunning outside of steals, although that is a trivial consideration in comparison) in the RAR figures--they cover offense and positional value only). This in no way means that I do not believe that fielding is an important consideration in player evaluation. However, two of the key principles of these stat reports are 1) not incorporating any data that is not readily available and 2) not simply including other people's results (of course I borrow heavily from other people's methods, but only adapting methodology that I can apply myself).

Any fielding metric worth its salt will fail to meet either criterion--they use zone data or play-by-play data which I do not have easy access to. I do not have a fielding metric that I have stapled together myself, and so I would have to simply lift other analysts' figures.

Setting the practical reason for not including fielding aside, I do have some reservations about lumping fielding and hitting value together in one number because of the obvious differences in reliability between offensive and fielding metrics. In theory, they absolutely should be put together. But in practice, I believe it would be better to regress the fielding metric to a point at which it would be roughly equivalent in reliability to the offensive metric.

Offensive metrics have error bars associated with them, too, of course, and in evaluating a single season's value, I don't care about the vagaries that we often lump together as "luck". Still, there are errors in our assessment of linear weight values and players that collect an unusual proportion of infield hits or hits to the left side, errors in estimation of park factor, and any number of other factors that make their events more or less valuable than an average event of that type.

Fielding metrics offer up all of that and more, as we cannot be nearly as certain of true successes and failures as we are when analyzing offense. Recent investigations, particularly by Colin Wyers, have raised even more questions about the level of uncertainty. So, even if I was including a fielding value, my approach would be to assume that the offensive value was 100% reliable (which it isn't), and regress the fielding metric relative to that (so if the offensive metric was actually 70% reliable, and the fielding metric 40% reliable, I'd treat the fielding metric as .4/.7 = 57% reliable when tacking it on, to illustrate with a simplified and completely made up example presuming that one could have a precise estimate of nebulous "reliability").

Given the inherent assumption of the offensive PADJ that all positions are equally valuable, once RAR has been figured for a player, fielding value can be accounted for by adding on his runs above average relative to a player at his own position. If there is a shortstop that is -2 runs defensively versus an average shortstop, he is without a doubt a plus defensive player, and a more valuable defensive player than a first baseman who was +1 run better than an average first baseman. Regardless, since it was implicitly assumed that they are both average defensively for their position when RAR was calculated, the shortstop will see his value docked two runs. This DOES NOT MEAN that the shortstop has been penalized for his defense. The whole process of accounting for positional differences, going from hitting RAR to positional RAR, has benefited him.

I've found that there is often confusion about the treatment of first baseman and designated hitters in my PADJ methodology, since I consider DHs as in the same pool as first baseman. The fact of the matter is that first baseman outhit DH. There are any number of potential explanations for this; DHs are often old or injured, players hit worse when DHing than they do when playing the field, etc. This actually helps first baseman, since the DHs drag the average production of the pool down, thus resulting in a lower replacement level than I would get if I considered first baseman alone.

However, this method does assume that a 1B and a DH have equal defensive value. Obviously, a DH has no defensive value. What I advocate to correct this is to treat a DH as a bad defensive first baseman, and thus knock another five or so runs off of his RAR for a full-time player. I do not incorporate this into the published numbers, but you should keep it in mind. However, there is no need to adjust the figures for first baseman upwards --the only necessary adjustment is to take the DHs down a notch.

Finally, I consider each player at his primary defensive position (defined as where he appears in the most games), and do not weight the PADJ by playing time. This does shortchange a player like Ben Zobrist (who saw significant time at a tougher position than his primary position), and unduly boost a player like Buster Posey (who logged a lot of games at a much easier position than his primary position). For most players, though, it doesn't matter much. I find it preferable to make manual adjustments for the unusual cases rather than add another layer of complexity to the whole endeavor.

2015 League

2015 Park Factors

2015 Teams

2015 Team Offense

2015 Team Defense

2015 AL Relievers

2015 NL Relievers

2015 AL Starters

2015 NL Starters

2015 AL Hitters

2015 NL Hitters

Thursday, October 22, 2015

End of Season Statistics, 2015

Monday, October 05, 2015

Crude Playoff Odds--2015

These are very simple playoff odds, based on my crude rating system for teams using an equal mix of W%, EW% (based on R/RA), PW% (based on RC/RCA), and 69 games of .500. They account for home field advantage by assuming a .500 team wins 54.5% of home games. They assume that a team's inherent strength is constant from game-to-game. They do not account for any number of factors that you would actually want to account for if you were serious about this, including but not limited to injuries, the current construction of the team rather than the aggregate seasonal performance, pitching rotations, estimated true talent of the players, and whatever Ned Yost sold to the devil.

These are the ratings that fuel the odds (CTR(H) is the team's rating with home field advantage included):

You'll note that the ratings love Houston much more than anyone else. thanks to their excellent EW% and PW%. The league disparity remains strong, with the average AL team (not playoff team) having a 107 rating with 100 being average. To the extent the ratings look odd, that is probably the largest driver; another is the fact that the NL East and West were the weakest divisions in MLB, so LA's SOS ranks 28th and NYN's ranks dead last. The Mets' average opponent is considered to be about equal to the White Sox; the Yankees' (who played the toughest schedule of any playoff team) is considered to be about equal to the...wait for it...Mets (actually, better than the Mets, 106 to 104).

The wildcard odds:

Very even matchups that actually slightly favor the visiting teams (remember, home team is assumed to win 54.5% if equal).

In the charts that follow, “P” is the probability that the series occurs; P(H win) is the probability that the home team wins should the series occur; and P(H) is the probability that the series occurs and that the home team wins [P*P(H win)].

LDS:

The series I was most interested in without looking at any numbers was NYN/LA; while it still ranks as pretty competitive, it's the least competitive on paper other than TEX/TOR. Surprisingly (but thankfully), KC should have their hands full every step of the way, although obviously wildcards burning off their pitchers is not accounted for here.

LCS:

The home team is favored in every LDS matchup, but that is decisively not the case here, with seven of the twelve possible LCS matchups featuring road favorites. This is due to the NL's top teams all hailing from the Central as the winner of STL/wildcard will be favored in any LCS matchup, along with TEX being considered the AL's weakest playoff participant but having home field should the wildcard knockoff KC.

World Series:

The NL is favored in just four of twenty-five possible matchups, namely those that feature the Rangers against not-the-Mets. STL is considered stronger than KC or NYA by the ratings, but home field advantage tips the odds to the junior circuit.

Putting it all together:

There's a 75% chance the World Series will be sufferable, which I think is decent. The AL has a 56.4% chance to win.

I lost a lot of Twitter followers last year by griping about the playoffs, particularly the Royals. So be it. The 2014 playoffs were the least enjoyable of my time as a fan. One factor was that the series weren't very good--there were a lot of sweeps and the like, until a terrific World Series. It wasn't extraordinarily bad in that respect, but there were fewer games than usual. There were a lot of very good individual games (at least until the World Series, which had an epic game seven that has washed away how blah most of it was out people's memories), but I'd prefer a better balance of series and game drama.

But what really irked me about the 2014 playoffs is how predictable they were. Many people praised the playoffs for their unpredictability, but I contend that in retrospect they were quite predictable in retrospect--the better team lost. Obviously the very existence of playoffs allows for the regular season results to be voided by short series results; too much so for my liking, as in my ideal world there would be four or two playoff teams (i.e. either 1969-1993 or pre-1969 format). The trend of history in every American sport is inexorably to further expand the playoff field.

I am fully aware of both of those facts--that short series often result in the lesser team winning, and that the playoffs are never going to be reduced in size. Accepting that reality does not, however, compel me to enjoy that reality, and I did not enjoy watching the better teams get beaten as a matter of course last October. I also find the style, attitude, and fan/media entitlement of the Royals to be insufferable, and thus I was particularly perturbed by the results.

At the risk of beating that dead horse, further points in my defense of my hatred of the 2014 postseason:

1. The better team almost always losing should not be what people mean when they say they like unpredictability in the playoff outcomes. That would involve the better team sometimes winning. It became very easy to predict (not with any assurance or confidence of accuracy in the moment, of course; I'm not suggesting the universe inevitably set the better teams to be defeated) the 2014 playoffs in short order after the horrid first set of games that saw three of four series go 2-0.

2. The Royals simply don't play the style of baseball I like. That's just my preference, not a sabermetric imperative or anything weighty like that, but I personally do not enjoy watching low secondary average baseball. Of course, the Royals started hitting home runs in the playoffs, so they were winning in large part due to the inverse of the narrative they were used to advance.

3. I don't begrudge anyone rooting for their team. Certainly I root for the Indians unequivocally when they are in the playoffs whether they are the best team or not. But it became really tiresome to hear about the Royals long playoff drought. I certainly do not believe that franchises are owed success thanks to fallow periods, but if I did, I would have started the list of worthy playoff participants elsewhere. After all, KC's drought was simply that they had gone thirty years without making the playoffs at all. They made the playoffs, they advanced from the wildcard round, they were in the playoffs. Why did that drought entitle their fans to more? The Tigers, Orioles, and Pirates all had longer World Series title droughts than the Royals. If people choose who to root for based on past suffering, the line should start there once you've advanced to the playoffs. There are a lot of fans of a lot of teams who have seen their teams make the playoffs multiple times and break their hearts once there, and they're supposed to pull for KC to win in their first shot? And while a thirty year playoff drought is excessive, a little bit of simple logic should tell you that given that there are thirty teams, thirty year world title droughts are not going to be even remotely remarkable in the future.

Hopefully this will be the last time I have occasion to rant about the 2014-15 Royals. May the Astros or Yankees do to them as they did to the Angels.

Tuesday, September 01, 2015

End of Season Stats Update

The end of season statistics I post have always walked a fine line between exhibiting a reasonable balance of accuracy and simplicity and veering to far into being needlessly inaccurate. That fundamental tension will not be removed with the changes I am making, but they will clean up a couple shortcuts that were too glaring for me to ignore any longer. I'm writing these changes up about a month in advance so that I don't have to devote any more space to them in the already bloated post that explains all the stats.

Runs Created

I've modified the knockoff version of Paul Johnson's Estimated Runs Produced that I use to calculate runs created to consider intentional walks, hit batters, and strikeouts. The idea behind using ERP, which is what I refer to as a "skeleton" form of linear weights, rather than using some other construct, is that I don't want to recalculate each and every weight every season. Instead, using fixed relationships between the various offensive events that hold fairly well across average modern major league environments is easy to work with from year-to-year and avoids giving the appearance of customization that explicit weights for each event would convey. Mind you, such a formula can still be expressed as x*S + y*D + z*T + ...

The previous version I was using was:

(TB + .8H + W + .7SB - CS - .3AB)*x, where x is around .322

To this formula I need to add IW and HB. This is all fairly straightforward--hit batters can count the same as walks, intentional walks will be half of a standard walk:

TB + .8H + W + HB - .5IW + .7SB - CS - .3AB

The rationale for counting intentional walks as half of a standard walk is that it is fairly close to correct (Tom Ruane's work suggests the ratio of IW value to standard walk value was .57 for 1960-2004). There are other possible approaches, such as removing IW altogether but assigning them the value of the batter's average plate appearance. There is certainly logic behind such a method; just doing it the simple way is a bit more conservative in terms of recognizing differences between batters.

Hit batters are actually slightly more valuable on average than walks due to the more random situations in which they occur, but such a distinction would be overkill given the approximate nature of the other coefficients.

I considered making adjustments for the other events included in the standard statistics (strikeouts, sacrifice hits, sacrifice flies, double plays) but ultimately chose to forego including each. The difference between a strikeout and a non-strikeout out is around .01 runs; given that there are numerous shortcuts already being taken, this is simply not enough for me to worry about in this context. Sacrifices and double plays are problematic due to the heavy contextual influences, although I came very close to just counting sacrifice flies the same as any other out. I would include K, SH, and SF if I was trying to do this precisely, but I would still leave double plays alone.

This was also a good opportunity to update the multipliers for all versions of the skeleton, which I did with the 2005-2014 major league totals to get these formulas:

ERP = (TB + .8H + W - .3AB)*.319 (had been using .324)

= .478S + .796D + 1.115T + 1.434HR + .319W - .096(AB - H)

ERP = (TB + .8H + W + .7SB - CS - .3AB)*.314 (had been using .322)

= .471S + .786D + 1.100T + 1.414HR + .314W + .220SB - .314CS - .094(AB - H)

ERP = (TB + .8H + W + HB - .5IW + .7SB - CS - .3AB)*.310

= .464S + .774D + 1.084T + 1.393HR + .310(W - IW + HB) + .155IW + .217SB - .310CS - .093(AB - H)

The expanded versions illustrate one of the weaknesses of the skeleton approach, or perhaps more precisely using total bases and hits rather than splitting out the hit types, as it results in the relationship between hit types being a bit off, particularly in the case of the triple. Still, I find the accuracy tradeoff acceptable for the purposes for which I use the end of season statistics.

For the batters who appeared in the 2014 end of season statistics, the biggest change switching to the version including HB and IW was five runs. Jon Jay, Carlos Gomez, and Mike Zunino gain five runs while Victor Martinez loses five runs. Of the 312 hitters, 263 (84%) change by no more than a run in either direction. So the differences are usually not material, another reason why I personally didn't mind the inaccuracy. But Carlos Gomez might disagree.

Along with the RC change are some necessary changes to other statistics. PA is now defined as AB + W + HB. OBA is (H + W + HB)/(AB + W + HB), and Secondary Average is (TB - H + W + HB)/AB, which is equal to SLG - BA + (OBA - BA)/(1 - OBA).

RAA for Pitchers

For as long as I've been running these reports, I've used the league run average as the baseline for Runs Above Average for both starters and relievers. This despite using very different replacement levels (128% of league average for starters and 111% for relievers). I've rationalized this somewhere, I'm sure, but the fundamental flaw is apparent when you look at my reliever reports and see three or four run gaps between RAA and RAR for many pitchers.

I want to avoid using the actual league average split for any given season, since it can bounce around and I'd rather use the league overall average in some manner. So my approach instead will be to look at the starter/reliever split in eRA (Run Average estimated based on component statistics, including actual hits allowed, so akin to Component ERA rather than FIP) for the last five league-seasons and see what makes sense.

The resulting difference in baseline between starters and relievers will not be as large as that exhibited in the replacement levels. The replacement level split attempts to estimate the true talent difference between the two roles, recognizing that most relievers would not be anywhere near as effective in a starting role. This adjustment is simply trying to compare an individual pitcher to what the composite league average pitcher would be estimated to have in his role (SP/RP) and does not account for our belief that the average starter is a better pitcher than the average reliever.

Additionally, using eRA rather than actual RA makes the adjustment more conservative than it otherwise might be, because it considers component performance rather than actual runs allowed. Part of the reliever advantage in RA is that the scoring rules benefit them. Why did I not then take this into account? I actually don't use RA in calculating pitcher RAA or RAR, I use a version of Relief RA, which was created by Sky Andrecheck and makes an adjustment for inherited runners (a simple one that doesn't consider base/out state, simply the percentage that score). The version I use considers bequeathed runners as well, so as to adjust starter's run averages for bullpen support as well. But the statistics on inherited and bequeathed runners by role for the league are not readily available, so I based the adjustment on eRA, which I already have calculated for each league-season broken out for starters and relievers.

This chart should be fairly self-explanatory: seRA is starter eRA, reRA is reliever eRA, eRA is the league eRA, s ratio = seRA/Lg(eRA), r ratio = reRA/Lg(eRA), and S IP% is the percentage of league innings thrown by starters. The relationships are fairly stable for the last five years, and so I have just used the simple average of the league-season s and r ratios to figure the adjustments.

RAA (for SP) = (LgRA*1.025 - RRA)*IP/9

RAA (for RP) = (LgRA*.951 - RRA)*IP/9

You can check my math as the weighted average of the adjustment is 1.025(.665) + .951(1 - .665) = 1.0002.

Sunday, August 16, 2015

Sunday, August 02, 2015

Great Moments in Yahoo! Box Scores

Am I surprised that Yahoo! box scores did not know how to handle SEA surrendering their DH position when Logan Morrison moved to first base? Of course not. It's still funny.

Thursday, July 23, 2015

1883 NL

The NL now had to share the major league stage with the AA, and it began to take act accordingly. Some combination of league “persuasion” and financial difficulty chased Troy and Worcester from the league. In their place, the NL returned to the two cities whose clubs were expelled after 1876, New York and Philadelphia. The two circuits would thus have their first head-to-head city battles.

Abraham Mills became the fourth president of the NL. According to Harold Seymour, one of his actions was to remove the team names from the official letterhead, as they tended to change so often. More significant changes were the expansion of the schedule to 98 games, switching to the Reach ball, eliminating first bound foul outs once and for all, and allowing the umpire to call for a new ball to be put in play at any time. These innovations were not copied by the upstart Association, with the exception of the expanded schedule.

Notable individual feats during the season included Monte Ward, now of New York, becoming the first pitcher to hit two homers in on game on May 3; Hoss Radbourn’s (PRO) 8-0 no-hitter against Cleveland on July 25 and One Arm Daily’s (CLE) 1-0 no-hitter versus hapless Philadelphia on September 13.

On May 30 (Memorial Day or Decoration Day or whatever it was called at the time), the NL tried a couple of two-city doubleheaders; Cleveland lost 3-1 at Boston, then won 5-2 at Providence. Taking their place was Buffalo, which started with a 4-2 loss in Providence and took the broom for the day as they lost 2-1 in Boston.

The pennant race was very competitive, with four teams in the mix. On July 7, Providence led the way at 33-16; Cleveland was two games back, but actually led by one in the loss column (30-15). Boston and defending champ Chicago were running third and fourth respectively. By August 20, Cleveland had the lead at 45-27 with Providence second. However, Cleveland lost two to Chicago and Providence two to Boston, bringing them right back into the hunt. The Reds went on to win six straight, but the Grays ended their streak and added another win in the first two of a series in Rhode Island. The third game on September 8 matched up the aces--Hoss Radbourn for the Grays and Jim Whitney for the Reds. Providence took the lead in the top of the eleventh, but Boston countered with two for a 4-3 win.

From that point on, Boston was in command, taking thirteen of fourteen and wrapping up the flag with a 4-1 victory over Cleveland on September 27. The final margin was four over the White Stockings, five over the Grays, and seven and a half over the Blues.

Perhaps Mills should have ordered some more stationary, as all eight clubs would be back. Peace with the AA came as well, but the tenuous new alliance would be tested immediately.

STANDINGS

The NL continued to boast fine competitive balance with the exception of Philadelphia. The actual records were pretty close to what the runs scored and allowed would suggest.

BOSTON

The Reds (who according to Nemec were also being referred to as the Beaneaters around this time, all informally of course) won their third NL pennant, pulling to within one of Chicago for the lead. It was a mild surprise as they were third and ten back in 1882, needing to pass both the White Stockings and their New England rivals, the Grays.

Rookies Mike Hines and Paul Radford were serviceable, while Edgar Smith was also a rookie but really was only the nominal regular in center field. He played thirty games in the outfield but Jim Whitney played forty, being used as a regular when not pitching for the first time. While his ARG was down a bit, the extra playing time made his bat more valuable and he had a better year pitching (his best so far in fact).

Rookie hurler Charlie Buffinton gave Boston a pair of good pitchers, something they had not had since two pitchers had become the norm. The duo’s combined WAR of over ten paced the circuit.

John Morrill was replaced by Jack Burdock as manager mid-season. Meanwhile, Arthur Soden was operating behind the scenes. He had claimed for a few years that the team’s profits needed to be reinvested to improve the club, but after he continued to sing that tune after the pennant, many of the shareholders gave in and sold out.

CHICAGO

The White Stockings kept their three-time pennant winning lineup largely intact; they cast off Hugh Nicol, shifted King Kelly back to the outfield, slid Tom Burns over to shortstop, and brought in Fred Pfeffer from Troy to play second.

If the second place finish must be laid at the feet of anyone, the previously brilliant pitching duo of Corcoran and Goldsmith would be the prime culprits. While they were still above average, they were now overshadowed by the Whitney/Buffinton duo in Boston and the Radbourn/replacement level #2 in Providence.

The White Stockings hammered Detroit 26-6 on September 6 on the strength of a record setting 18 runs in the seventh inning.

PROVIDENCE

The Grays continued to close the gap on Chicago; since winning the 1879 flag, they had finished 15 behind Chicago, then nine, three, and finally one. Unfortunately for them, that meant a third place finish in 1883.

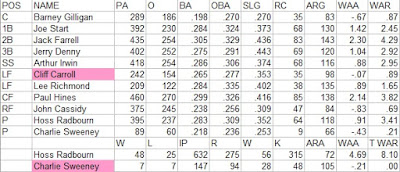

The team brought in three regulars from the defunct franchises; Arthur Irwin and Lee Richmond (the team’s #3 pitcher with 94 innings) from Worchester and John Cassidy from Troy. Rookie Cliff Carroll shared left with Richmond, and rookie Charlie Sweeney turned in a replacement-level performance as the #2 pitcher. With Radbourn earning his “Hoss” moniker by tossing 632 innings with the league’s best ARA, that was adequate enough.

There were rumors late in the summer that the club’s board of directors was going to close shop and instead shift their sporting interests to harness racing. Instead, perhaps due to displeasure over the supposed scheme, they voted to distribute the profits, then resigned. Providence would continue as a member of the National League.

CLEVELAND

The Blues picked up Bushong and Evans from Worcester, Daily from Buffalo, York from Providence, and Hotaling from Boston (he had played for Cleveland in 1880 as a rookie). They managed to get into contention largely on the strength of their brilliant keystone combo of Dunlap and Glasscock, both of whom I see as the all-star at their position for 1881-1883.

Had they combined the pitching they had boasted in previous years with this offense, they may have done more than just contend. Jim McCormick’s workload plummeted from 596 to 342 innings despite the expanded schedule (although his ARA held steady at 86). Neither One Arm Daily nor nineteen year old Will Sawyer, in his only big league campaign, contributed any value.

The Blues visited the White House in April. President Chester Arthur spoke to them, advising that “good ballplayers make good citizens”.

BUFFALO

The Bisons finished with the same W% (.536) that they had in 1882. This is not too surprising as they returned all their regulars except Blondie Purcell (now with Philly) and One Arm Daily (Cleveland). However, Curry Foley was sidelined with various maladies of the joints, and only got 115 PA. Rookie Jim Lillie took his place in center field (see Brian McKenna’s thread on Foley at Baseball-Fever for more).

A profit of $5,000 was turned, which they put towards a new ballpark that, according to Phil Lowry in Green Cathedrals, cost $6,000. The team also wore new blue uniforms this season; ace Pud Galvin objected on the grounds that they made him look fat. No, Pud, the fat made you look fat.

NEW YORK

The Gothams were controlled by John Day and Jim Mutrie, who also controlled the Metropolitans, the formerly independent and now AA club. Some players were shifted from the Mets to the Gothams, but around half of the New York regulars had played in the NL in 1882.

The top source of players was Troy, from whence came Ewing, Connor, Gillespie, and Welch (Hankinson and Caskin had last seen NL action with the Trojans in 1881). Dasher Troy came from Detroit (Dorgan had last played in the league with the Wolverines in 1881), Monte Ward from Providence, and Tip O’Neill was the lone rookie on the team. Given their wealth of experience for a first-year club, it is not surprising that they finished a respectable 46-50.

John Clapp was the manager of the team; he was also a reserve catcher (78 PA). This would make the end of Clapp’s remarkable major league career in which he managed six different teams all for one season each: the Mansfields of Middletown, CT in 1872; then, for four straight years beginning in 1878, Indianapolis, Buffalo, Cincinnati, and Cleveland; and finally the 1883 New Yorks.

The team’s debut, which was the first NL game ever played in New York City (the 1876 Mutuals actually played in Brooklyn which was a separate municipality at the time), was a 7-5 victory over eventual pennant winner Boston. The crowd included ex-President Ulysses S. Grant.

DETROIT

The Wolverines were mired near the bottom of the heap again; they had slipped to sixth and now seventh after an encouraging fourth in their inaugural campaign. Sam Trott, a reserve in 1882, moved into the lineup, and they regained the services of Sadie Houck who had not played in 1882. Tom Mansell split right field duties with rookie Dick Burns after having not played in the NL since 1879 with Syracuse. Burns and another rookie, Dupee Shaw, teamed up with Stump Wiedman as the primary pitchers.

PHILADELPHIA

It was a tough first year for the Phillies. The NL, seeking to get into Philadelphia where the AA’s Athletics had been a success, recruited Al Reach to back the team; he and partner Ben Shibe went in with lawyer John Rogers.

It may not be historically kosher, but I like to think of this club as the first expansion team in the modern sense. Most previous “expansions” had simply brought strong independent clubs into the circuit, but the Phillies included a group of castoffs and minor leaguers that more closely resembles modern expansion team composition. Their pathetic 17-81 record, worst in the NL since the league’s inaugural season (Cincinnati, 9-56) certainly doesn’t hurt the argument. They also used 29 players, a huge number for the time--the next highest was Buffalo with 18 and the median was 16.

Of the regulars, Ringo, Farrar, Coleman, and Hagan were rookies. The rest of the players (and last ML experience; 1882 if not listed): Gross (PRO, 1881), Ferguson (TRO), Warner (CLE, 1879), McClellan (PRO, 1881), Purcell (BUF), Harbidge (TRO), and Manning (BUF, 1881).

On Aguust 21, the Phillies were hammered 28-0 at Providence. Art Hagan was a Rhode Island native, and was left in to absorb the shellacking as the team did not want to disappoint the hometown fans that had come out to see him.

It was not a good year at the box office either, as the Athletics were reported to draw twice as many fans as any NL team and four times as many as the Phililies. Bob Ferguson quit as manager mid-season and was replaced by Blondie Purcell.

Leaders and trailers:

BATTING AVERAGE

1. Dan Brouthers, BUF (.374)

2. Roger Connor, NYN (.357)

3. George Gore, CHN (.334)

Trailer: Doc Bushong, CLE (.172)

ON BASE AVERAGE

1. Dan Brouthers, BUF (.397)

2. Roger Connor, NYN (.394)

3. George Gore, CHN (.377)

Trailer: Stump Wiedman, DET (.196)

Trailing non-pitcher: Doc Bushong, CLE (.198)

SLUGGING AVERAGE

1. Dan Brouthers, BUF (.572)

2. John Morrill, BSN (.525)

3. Roger Connor, NYN (.506)

Trailer: Doc Bushong, CLE (.195)

SECONDARY AVERAGE

1. John Morrill, BSN (.243)

2. Charlie Bennett, DET (.240)

3. Dan Brouthers, BUF (.235)

Trailer: Stump Wiedman, DET (.048)

Trailing non-pitcher: Doc Bushong, CLE (.056)

RUNS CREATED

1. Dan Brouthers, BUF (112)

2. Roger Connor, NYN (102)

3. Ezra Sutton, BSN (92)

4. George Gore, CHN (92)

5. Jim O’Rourke, BUF (91)

The expanded schedule enabled Brouthers and Connor to become the first National Leaguers to create an estimated 100 runs in a season.

ARG

1. Fred Dunlap, CLE (194)

2. Dan Brouthers, BUF (191)

3. Roger Connor, NYN (189)

4. Ezra Sutton, BSN (159)

5. George Gore, CHN (157)

Trailer: Stump Wiedman, DET (45)

Trailing non-pitcher: Frank Ringo, PHI (53)

WAA

1. Fred Dunlap, CLE (+4.5)

2. Dan Brouthers, BUF (+4.4)

3. Roger Connor, NYN (+4.2)

4. Ezra Sutton, BSN (+3.0)

5. George Gore, CHN (+2.7)

Trailer: Stump Wiedman, DET (-2.6)

Trailing non-pitcher: Davy Force, BUF (-2.0)

WAR

1. Fred Dunlap, CLE (+6.4)

2. Dan Brouthers, BUF (+5.4)

3. Roger Connor, NYN (+5.3)

4. Ezra Sutton, BSN (+4.8)

5. Buck Ewing, NYN (+4.4)

Trailer: John Humphries, NYN (-.9)

Humphries was the Gothams’ #2 catcher behind Ewing. He made 85 outs in 108 PA, hitting .112/.120/.121 and creating just one run. Another Gotham reserve, outfielder Gracie Pierce, is next on the trailing list, making 50 outs in 63 PA, hitting .081/.095/.113 and creating just one run.

ARA

1. Hoss Radbourn, PRO (72)

2. Jim Whitney, BSN (74)

3. Charlie Buffinton, BSN (83)

4. Larry Corcoran, CHN (86)

5. Jim McCormick, CLE (86)

Trailer: Art Hagan, PHI (178)

WAA

1. Hoss Radbourn, PRO (+4.7)

2. Jim Whitney, BSN (+3.4)

3. Pud Galvin, BUF (+2.1)

4. Larry Corcoran, CHN (+1.7)

5. Charlie Buffinton, BSN (+1.5)

Trailer: John Coleman, PHI (-7.5)

T WAR

1. Hoss Radbourn, PRO (+8.1)

2. Jim Whitney, BSN (+7.8)

3. Charlie Buffinton, BSN (+2.8)

4. Pud Galvin, BUF (+2.2)

5. Monte Ward, NYN (+2.1)

Trailer: John Coleman, PHI (-5.6)

My all-star team:

C: Buck Ewing, NYN

1B: Dan Brouthers, BUF

2B: Fred Dunlap, CLE

3B: Ezra Sutton, BSN

SS: Jack Glasscock, CLE

LF: George Wood, DET

CF: George Gore, CHN

RF: Orator Shaffer, BUF

P: Hoss Radbourn, PRO

P: Jim Whitney, BSN

P: Charlie Buffinton, BSN

MVP: 2B Fred Dunlap, CLE

Rookie Hitter: C Mike Hines, BSN

Rookie Pitcher: Charlie Buffinton, BSN

I gave George Wood the nod in left field as he was close to the top in WAR (Tom York and Jim O’Rourke were in the mix as well), but Pete Palmer has him at +7 in the field, easily the best of those three. Again, the right fielders were a weak crop; Paul Hines, the runner-up in center field, was 1.7 WAR better than Shaffer.

The pitchers were the same pair as last season, but in reverse order. Radbourn led the league in ARA (meaning he was the most effective on a per inning basis) and tossed 632 innings, second only to Pud Galvin’s 656, an unbeatable combination even for Whitney’s bat. I also added a third spot as the AA averaged close to three 100 IP pitchers per team.

It was another very weak year for rookie hitters; while Mike Hines only put up a 70 ARG, I felt that being the catcher for a pennant-winning team should probably count for something--and it’s not as if he’s taking it away from a guy who had a great year (the top rookie hitter in WAR is Cliff Carroll, +.9 and also a below-average hitter).

Saturday, July 11, 2015

Collapse, pt. 2

For the second time in three years, OSU baseball entered May in excellent position to secure the program's first NCAA tournament berth since 2009, projected as a #2 seed with an outside shot of earning a #1 and hosting a regional. For the second time in three years, it all came crashing down around hapless coach Greg Beals. This one was even tougher to swallow. In 2013, the crash mostly came in non-conference games against tough national opponents (Georgia Tech, Louisville, Oregon), and the Buckeyes still came close to a share of the Big Ten title. In 2015, OSU tumbled down the Big Ten standings, losing eight of their final nine conference games to fall to seventh in the league.

Despite this catastrophic failure, the stagnation of the program under Beals' stewardship, and the expiration of his inital contract, it appears as if Beals will be invited back for a sixth season leading the OSU baseball program. Under previous coach Bob Todd, the Buckeyes and Minnesota duked it out for conference supremacy, a veritable big two and little eight on the diamond. While Todd's program slipped a bit near the end of his tenure, he still made semi-annual NCAA appearances and captured a final regular season crown in 2009. Under Beals, OSU has clearly fallen behind at least Indiana, Illinois, and newcomers Nebraska and Maryland in the Big Ten pecking order.

The Big Ten got five teams into the NCAA Tournament: Indiana, Iowa, the forces of evil, Maryland, and Illinois, with the latter two winning their regionals. But the overall performance of conference teams only adds to the frustration for OSU supporters, as the Bucks finished 35-19 (.648), third in the Big Ten (Illinois led at 50-10, .833). In EW%, OSU was fifth at .636 (Illinois led at .783), and in PW% OSU was third at .643 (again, the Illini led at .748). OSU tied for fourth with 5.63 runs/game against a conference average of 5.36 and sixth with 4.22 RA/game against an average of 4.87.

OSU's offense was paced by its outfield, with the three primary starters ranking 1-2-3 on the team in RAA. Sophomore left fielder Ronnie Dawson took a step back from his debut campaign, but still hit .279/.357/.465, ranked second on the team with 7 longballs, and created 6.3 RG for +9 RAA. Classmate leadoff man and center fielder Troy Montgomery broke out in a big way, hitting .317/.424/.493 for 8.7 RG and +22 RAA. And senior right fielder Pat Porter played himself into being a fifteenth round pick of Houston with a bounceback .338/.414/.576, eleven homer, 9.4 RG, +25 RAA season that also saw him set the school's career triples record.

The platoon of senior catchers Aaron Gretz and Conor Sabanosh was fairly effective, with 176 and 189 PA respectively, Gretz created 6.1 runs/game and +5 RAA, Sabanosh 5.0 and +1, although it once again mystified this observer that Beals showed a degree favoritism towards Sabanosh in doling out playing time. First base was a major weakness. Jacob Bosiokovic missed most of the season, taking one option out of play. Junior Ryan Leffel struggled at the plate, hitting .211/.304/.267 for 3.3 RG and -4 RAA in 109 PA, while classmate Zach Ratcliff hit well (7.1 RG) in limited opportunities (64 PA). Eventually junior Troy Kuhn saw time at first after starting the season at the hot corner, and was Ohio's most productive infielder with 5.4 RG for +2 RAA in 187 PA.

After Kuhn shifted across, the diamond, junior second baseman Nick Sergakis moved to third. Sergakis did not reprise his strong 2014 campaign with a .250/.320/.330, 4.3 RG, -3 RAA season. Sophomore L Grant Davis plugged in at second, hitting .282/.320/.353, 4.7 RG, -1 RAA over 102 PA. And an early hot streak kept junior Craig Nennig from a third straight dismal offensive performance, but he still only hit .266/.327/.330 for 4.3 RG and -3 RAA.

There was no regular DH, so the only other Buckeye who got more than 50 PA was freshman outfielder Tre' Gantt, who showed promise with speed and a .311/.378/.351, 5.6 RG, +2 RAA performance over 85 PA--he should be a shoe-in for the vacant outfield spot. Freshman catcher/DH/pinch-hitter Jordan McDonough showed some gap power with six doubles in 41 PA (4.7 RG). Sophomore IF/C Jalen Washington and junior OF Jake Brobst served mostly in pinch-running roles, combining for just 37 PA.

OSU's starting pitching was solid, but that's about the strongest praise that can be offered. Sophomore lefty Tanner Tully was slotted as the #1 but not surprisingly took a big step back from his Freshman of the Year campaign with a 5.04 RA (and even more distressing 5.75 eRA) and -3 RAA over 75 innings. His strikeout rate ticked up from 5.1 to 5.3, which tells much of the story. Sophomore Travis Lakins moved into the rotation but was just average (4.78 RA for -1 RAA with a similar eRA in 96 innings), but clearly was the best mound prospect on the team and was draft eligible, signing with Boston after being a sixth round pick. Senior Ryan Riga was OSU's best pitcher and was drafted in the thirteen round by the White Sox after positing a 3.38 RA for +12 RAA over 97 innings).

Freshman Jacob Niggemeyer got the most mid-week starting assignments with seven, but will need to improve on a 4.09 RA, 5.35 eRA, and 4.1 K/9 performance to be a strong candidate for weekend starts in 2016. Redshirt freshman Adam Niemeyer worked in something of a long relief role, pitching 33 innings over 12 appearances (4 starts) with a 2.16 RA and 3.79 eRA for +9 RAA to rank second to Riga on the team. Junior lefty John Havird (3.58 RA, 4.17 eRA in 27 innings) will also be in that mix.

The Buckeye bullpen struggled immensely, particularly down the stretch and in the Big Ten Tournament. In the last regular season weekend at Indiana, the bullpen failed to hold a 4-3 eighth inning lead in the opener, then surrendered two runs with the game tied in the eighth in the finale. In the Tournament, closer Trace Dempsey yielded a two-out, two-strike homer in the opener against Iowa that turned a 2-1 lead into a 3-2 loss. Scarred by the experience, Beals stuck with his ace Riga in the eighth inning of a 2-2 elimination game against the Hoosiers; they struck for three and ended OSU's season, 5-3.

Dempsey's senior season saw him once again unable to catch his sophomore lightning in a bottle--he was average but not brilliant (4.46 RA, 3.98 eRA, +1 RAA, with 8.4 K/9 against 2.4 W/9, the latter a marked improvement from 4.9 in 2014). The rest of the pen was weakened by a late season injury to junior Jake Post, who was the best Buckeye reliever with a 3.03 RA, 4.05 eRA, +6 RAA over 29 innings. Freshman Seth Kinker pitched well (2.82 RA with similar eRA for +5 RAA, 7.7 K/1.2 W over 22 innings0 and marks a continuation of one of the few positives of Beals' style--a fondness for relievers with less than over-the-top deliveries. As the season progressed Kinker took some high leverage work away from redshirt freshman Kyle Michalik, who pitched better than his traditional stats might indicate, albeit in only 19 innings (5.21 RA but 2.92 eRA). Senior Michael Horejsei really only had his left-handedness to offer him as a key reliever, ranking second to Dempsey with 19 appearances but tossing just 14 1/3 innings with a 6.91 RA and 5.57 eRA. Redshirt sophomore Shea Murray came back from an arm injury to throw seven ineffective but exciting innings (7.04 RA, 4.7 W, 14.1 K); his stuff was good enough for Texas to take a flier on him in the 39th round.

As far as the state of the program goes, there's really nothing to be said that I haven't already. Perhaps one could credit Beals for some apparent development by offensive players (Montgomery in particular comes to mind), but his track record in that regard is still quite sketchy. The dreadful baserunning and bizarre infatuation with the runners at the corners, two out double steal show no sign of abating, the late season collapse is fast becoming a staple, and while a 35-20 record doesn't look so bad, Beals' five-year body of work is 159-125 (.560), the program's worst stretch of that length since 1986-1990 (.500), except for the overlapping 2010-2014 period (.543). The same holds true for conference play where Beals is 49-47 (.510). The six-year NCAA Tournament drought is the longest since OSU went eight years without qualifying 1983-1990. It's time for OSU to once again have a baseball program its football and basketball programs can be proud of, and it seems likely that someone other than Beals would be best positioned to make that happen.