One of the many old books available for full download on Google Books is/was Henry Chadwick’s 1874 Chadwick’s Base Ball Manual. (Since I wrote this piece and downloaded the book, the full-text PDF version of the book appears to have disappeared from Google Books, or at least I cannot find it.). The specific edition I have linked was published in London by George Routledge and Sons. As Chadwick explains in the introduction, “The advent of the American base ball players in England bids fair to bring about the introduction of a new game into the extended circle of British sports and pastimes, and one, too, well calculated to achieve a popularity second only to that of the English national game of cricket; and this new field sport is the American game of BASE BALL. Though of English origin, this game is fully entitled to the name of American, and it is a sport just suited to the peculiar temperament of the people of that great republic, as it is full of excitement, occupies but little time, and can be engaged in with equal zest by the youngest schoolboys or by trained professional ball players, to the latter of whom it affords full scope for the exercise of those mental as well as physical attributes which mark the intelligent and cultured athlete.”

In typical Chadwick fashion, these two sentences encompass 149 words. Anyway, the takeaway is that this particular edition of the book was prepared for an English audience in the hopes that baseball would emerge as a major sport in that country. Of course, as we all know, Chadwick’s optimism was unfounded, and baseball has never taken off across the pond, although there devoted British fans certainly do exist.

The portion of the book that I am going to focus on here doesn’t do justice to the work as a whole, but I’ll let you explore that on your own if you are so inclined. Here is a little tease from page 27 as Chadwick describes the role of the “short fielders”:

In the present position of the game there is but one “short-stop”, and he stands to the left of the infield between the second and third base positions. Ultimately, however, a “right-short” will be introduced, which will make the field one of ten men instead of nine, as now.

It is unfair to Mr. Chadwick that I have quoted two passages in which he is 0-2 at predicting on the future of the game (although in this case, ten men and ten innings was something of a personal crusade, and perhaps he hoped that writing a forecast with such confidence would encourage the spread of the ten-man game). My point is not to mock his errors in prognostication, but rather to illustrate what an interesting period piece this is, and what a great window it is into the mind of one of the most influential men in baseball history.

What I want to focus on here is Chadwick’s scoring system. As the premier early baseball writer, Chadwick’s influence was felt far and wide, and so his early system of scorekeeping influenced those that came later, and still influences the standard scorekeeping of today.

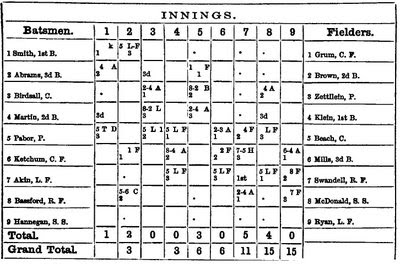

Pages 33-43 of the book discuss Chadwick’s scoring system, and if you are interested I’d encourage you to read them for yourself. I am just going to give a brief summary and reproduce the sample scoresheet that Chadwick includes. This sheet is for the batting of the Unions in their game against the Eckfords of Brooklyn on June 6, 1866:

The most striking similarity to modern scorekeeping is in the general layout of the grid, which for the standard method of scoring has scarcely changed. Nine rows for the batting order, and nine columns for each of the innings in which their performance is recorded. Chadwick reproduces the opposing fielders as well on the far side of the page. While some modern scoresheets (particularly those used by announcers) include the opponents’ fielders for reference purposes, it was pretty much a necessity to have that information at hand if scoring by Chadwick’s system, as we shall see.

What is most strikingly different about Chadwick’s scoring method? The fact that there is no record of how a batter reached base, or how he advanced around the bases takes the cake. As you can verify by checking the runs tally for each inning at the bottom of the page, the solid dots indicate that the player scored a run. For any player that didn’t score a run, there is notation to record how they were retired, or where on the bases they were stranded.

The numbers placed on the extreme left of each scorebox indicate the out number in the course of the inning. So in the first, the “1” in Smith’s box indicates he was the first out; the “2” in Abrams’ that he was the second; and the “3” in Pabor’s that he was the third.

The “k” in Smith’s box indicates that he was a strikeout victim, just as it would today. As Chadwick explains, the letter K [indicates] how [the batter was] put out, K being the last letter of the word “struck.” The letter K is used in this instance as being easier to remember in connection with the word struck than S, the first letter, would be.

This guiding principle in establishing letter codes is further illustrated by Chadwick’s use of “L” for a foul ball (also used undoubtedly because “F” is already reserved for a fly) and “D” for a catch on the bound (in early baseball, catches made on the first bound were fair, and even once the NL had been established there was a period of times in which outs could be recorded on a foul caught on the first bounce). The other important letter codes are “A” for a runner retired at first, “B” for a runner retired at second, “C” for a runner retired at third, “H” for a runner retired at home, “T” for a foul tip, and “R” for a runner put out between bases. Various combinations could be formed form these.

Thus, in the first inning we can see that Abrams was retired at first and that Pabor was retired “T D”--a tip caught on the bound, combining those two codes. But what does the “4” that precedes A indicate in Abrams’ box, and the “5” that preceded T D in Pabor’s?

It means that the fielder who bats fourth in the opposing order made the play on Abrams, and now we see why it was imperative that the opponents’ batting order be reproduced on the page--Chadwick identified fielders by their lineup slot, not by the position numbers we use today. Thus it makes sense that Pabor’s “5” reflects on the catcher of the Eckfords, who we would obviously expect to make the play on a foul tip.

As seen later in the sheet, assisted putouts are recorded in a similar fashion as we still do today. In the fourth, Ketchum was out at first “8-4”, which a glance at the Eckford lineup reveals to be a routine 6-3 in today’s shorthand.

The scoring for runners left on base is straight forward--the “3d” in Martin’s first inning box (or Abrams’ third or Martin’s eighth) simply indicates that he was stranded on third. Likewise, Akin was stranded on first in the seventh, and no Union runner was stranded on second in this contest.

Of note is an oddity that could not be seen in modern baseball, which is that in the third, the Unions’ last batter was Pabor, and he completed his plate appearance by fouling to the catcher (at least as far as I can tell; I’m not exactly sure what the “1” or lower case “l” is supposed to signify). The third out was made by Martin, who apparently was already on base.

Under the rules of the time, it was the man in the lineup who followed the last man retired who would lead off the next inning, not the man in the lineup who followed the last man to complete a plate appearance, and so Pabor led off the fourth…and again fouled to the catcher, although this time the notation clearly indicates it was a foul fly.

While this is all very interesting in its own right for a scorekeeping aficionado like myself, I am now going to launch into a digression about the relationship between Chadwick’s scoring and early statistics. As those of you that have read works like The Hidden Game of Baseball (John Thorn and Pete Palmer) or The Numbers Game (Alan Schwarz) already know, early box scores didn’t contain very much in the way of offensive data. The earliest included just runs and hits, and often contained much more detail on fielding (specifically putouts, assists, and errors).

If one’s only objective in scoring a game was to record runs and outs along with detailed fielding statistics, than the system used in this example by Chadwick makes perfect sense. Why bother recording how a runner reached base, or how many bases his hit was worth, if that information was not going to be recorded for posterity? (However, in the Manual cited here, Chadwick does explain a system for recording that type of information. Interestingly, though, he describes it as a “reporting” system, necessary for “reporting a game for a detailed description in a journal.” In other words, he would include these types of details in his account of the game, but not in the accompanying box score).

The decision to record just runs and outs was not as misguided in its own time as it would be today. It was a different game, then, one in which extra base hits and walks were not terribly common, there was a large number of errors, and a high percentage of batters who reached base wound up scoring (In the case of the Unions for whom Chadwick reproduced a scoresheet, 15 runs were scored with just three stranded. I’m not claiming that was representative of a typical game at the time, but it certainly can serve as a singular data point in that discussion). Knowing just the number of outs a player made and the number of runs he scored told you much more about his real value than such data would today.

Of course, more detailed data was collected in short order, and batting average overtook runs as the most important individual offensive category. In one sense this was obviously a positive development, as it attempted to remove from the batter’s record the influence of his teammates (in another, of course, it was negative as it would enshrine batting average as the number one offensive indicator for a century to come, even when further developments in the game made BA’s alleged superiority even more questionable) . But one thing that was largely lost in the shuffle was the importance of outs as the proper (*) context in which to view offensive performance.

I wonder if or how the development of conventional statistical wisdom would have been altered had the box score column remained “outs” instead of “at bats”. The move to at bats obscured the fact that at bats = outs + hits. By hiding the outs in the broader category of “at bats”, which are easily dismissed as simply a playing time measure, they were hidden from the view of casual fans.

Of course, unless you also consider walks, the result might be the same; valuing hits in relationship to outs is ultimately the same as valuing them in relationship to at bats. But if a hits/outs ratio was used rather than a hits/at bats ratio, there would be many more people who would inherently accept that outs are the proper denominator for an overall offensive rate stat. One of the big steps in converting a lot of people to a sabermetric outlook is to convince them that using outs and not just total opportunities (AB or PA) results in the best model of true offensive value.

People have no trouble accepting innings pitched as the denominator for many pitching statistics, as of course everyone understands that is how ERA is calculated. But mainstream views on pitching statistics also benefit from the fact that innings are thought of as the measure of playing time, despite the fact that batters faced makes more sense from that narrow standpoint.

The average fan thinks about a batter’s playing time in terms of AB or PA, and a pitcher’s in terms of innings. Then when he wants to state the batter’s productivity, he thinks of it terms of AB or PA, while accepting innings for pitchers. My claim is that these two are connected, as those not of a sabermetric bent generally don’t spend much time thinking about these things.

In fairness to casual fans, there is reason to think that the denominator of an overall productivity measure should be different for pitchers and hitters--since the pitcher stands alone, it is obvious to put him in team (outs) context, while a batter is just one of nine. But again, I doubt that many non-sabermetricians have thought too deeply along those lines.

To tie this digression back to Chadwick, I wonder what the conventional wisdom would be today had outs remained prominent in the box score rather than been pushed aside by at bats, and had the relationship between runs and outs remained at the center of batting statistics.

(*) At least close enough. I know as well as anybody that there are other approaches like RAA/PA and R+/PA and R+/O+ and the list goes on, so don’t leave any anonymous comments on this point.

Monday, April 20, 2009

Keeping Score With Henry Chadwick

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

I thoroughly enjoyed this post. Any chance I could email you and get a copy of the PDF download?

ReplyDeleteUnfortunately for both of us, no. Believe it or not, my hard drive crashed last night, and I had not yet backed up the file.

ReplyDeleteI don't understand why it is gone from Google Books, and perhaps it is still there and I am just too dumb to find it (either way, Google Books' search function is pretty pathetic considering they are the world's leading search engine. Searching for "chadwick base ball manual" yields nothing--it was only after entering Chadwick as the author and Routledge as the publisher that I was even able to find the skeletal information linked in the post).

I was going to ask the same question. Bummer that your hard drive crashed. Bad timing, eh?

ReplyDeleteAnd I second you on Google's book search. For as great as Google is in so many things, and for as fantastic of a service as Google Book Search is, they've really done a terrible job of giving the user something easy to use. I'll try to play around with the Book Search... maybe there's some way to game the system!

I wouldn't mind a copy either.

ReplyDeleteJust as a side note, '81 Squares' would have been a great name for this blog.

As I said, I lost my copy of the file, so I can't accommodate any requests. If I'm able to recover the file (doubtful) or find it again on Google somehow, I'll be sure to let you guys know.

ReplyDelete81 Squares would be a good blog name, particularly for my (or any) scorekeeping blog. As you can see from the title of this blog, creativity isn't exactly my strong suit.